David Soskice, The Secrets Of The Schluesselburg (1909)

Soskice, David, ‘The Secrets Of The Schluesselburg’, McClure’s Magazine, 34.2 (1909), 144–63

THE SECRETS OF THE SCHLUESSELBURG

CHAPTERS FROM THE SECRET HISTORY OF RUSSIA’S MOST TERRIBLE POLITICAL PRISON

BY DAVID SOSKICE

WITH AN INTRODUCTION BY MISS CATHER

ILLUSTRATED WITH DRAWINGS AND PHOTOGRAPHS

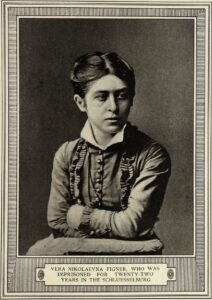

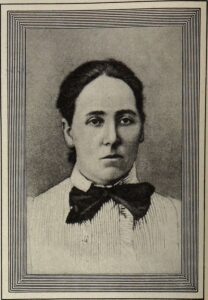

ON the night of the 23d of June, five months ago, the Russian colony of London met at South Place Institute, Finsbury, to welcome Mme. Vera Nikolaevna Figner, who must be regarded as the heroine of the following narrative. The hall was crowded with Russian exiles of every degree, and on the platform, among the revolutionary leaders, sat several of Mme. Figner’s old comrades of the party of “the People’s Will.” When Mme. Figner entered on the arm of the Chairman, the house rose and broke into cheers. We saw a small, slender woman, who wore a white evening gown and carried a bunch of flowers. After twenty-two years in a cell, deprived of even the meanest accessories to bodily well-being, and weeks in the “black hole,” with not even a blanket between her and the damp stone floor, she looked but little older than other women of her years. It was only when her face was in complete repose, and after the flush of excitement had left it, that one saw there the marks of terrible suffering.

In introducing Mme. Figner, M. Volkovsky said, in brief:

“The English Government is at this time preparing to welcome to this country the Tsar,

144

145

Nicholas II., as the representative of the great Russian people. But we, and many thousands of our brothers, refuse to recognize in the author of Bloody Sunday a representative of our fatherland. We have with us to-night, in Vera Nikolaevna, Mme. Figner, a true representative of the Russian people; for she has in her own person known all its sorrows and all its aspirations.”

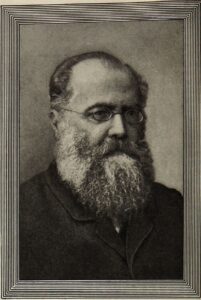

Prince Kropotkin and Dr. David Soskice, author of the following article, addressed the audience in English, and Mme. Figner herself made a long speech in Russian. Her address was a purely political one. She said very little about her own imprisonment, and only once or twice did the English listener catch the ominous word, “Schluesselburga.” Mme. Figner used no notes, and spoke entirely without excitement, seldom unclasping her gloved hands. The shrill night-noises of a crowded London quarter which came in through the open windows did not perceptibly disturb her — a remarkable instance of her self-control, when one remembers how much she still suffers from sudden or unexpected sounds. After hearing Mme. Figner speak, it is easy to believe that her brother is one of the greatest singers in Russia. Her own voice is one of marvelous resonance and power, beautifully modulated in spite of the fact that it was mute for so many years.

Although Prince Kropotkin translated the substance of her speech, Mme. Figner had intended to make a second address in English, but was too tired to do so. She studied English and Italian grammars in prison, memorizing a large vocabulary in both languages. Arriving in London at the age of fifty-eight, and never having spoken the tongue, she was able in three weeks to converse in English with considerable fluency, and is rapidly perfecting herself in the language, as she contemplates coming to America. It is easy to understand why, when the Tsar at last ordered her release from the Schluesselburg, Plehve said: “There is still too much life left in her.”

— W. S. C.

I

IN the middle of the River Neva, where it flows out of Lake Ladoga, there lies a tiny island, surrounded on three sides by the mighty, turbulent waters of the river, and hemmed in upon the fourth by the cold and stormy lake. Upon this island stands a very ancient fortress, inclosed by high walls more than twenty feet in thickness. This is the Fortress of Schluesselburg. Day and night, sentinels relieved every two hours

pace around the top of these walls, keeping a vigilant lookout on every hand. No one from within the fortress, not even the soldiers or gendarmes, is allowed to communicate with the people who dwell upon the banks of the river. If an unwary fisherman chances to drift in his boat too near to the walls of the fortress, he is greeted by the shout of a sentinel, aiming his rifle:

“Away! Or I shoot!”

Not even the Dead Sea in the deserts of Asia is so utterly isolated and cut off from the living world as is this Fortress of Schluesselburg, which lies within forty miles of St. Petersburg.

They are very ancient, the high walls of the fortress. In many places they are cracked from old age, and in the cracks little trees have taken root. The lower part of the walls has gradually become covered with thick dark moss, just as the face of a very aged man becomes covered all over with hair. They look sullen and ominously silent, as if they hid dark and gruesome secrets. And, in truth, in the whole world there are no other walls that have witnessed so many and such terrible human tragedies as those of the Fortress of Schluesselburg. Since, two centuries ago, it passed from the hands of the Swedes into those of the Tsars, it has played a part in the darkest deeds of the Russian Emperors. Each new sovereign has interred within its narrow cells all those whom he found distasteful or considered embarrassing to him.

Peter the Great in 1698 grew tired of his wife, Evdokia Lopukhina, and to get rid of her he forced her, a beautiful woman of twenty-five, to enter a convent. The unhappy young Tsarina was not even allowed to take an attendant with her. In the flower of her beauty and youth, she was compelled to live the life of a working nun, without a ray of hope or consolation, while her husband took to himself another wife, who became the Empress Catherine I. Every nerve of the young deposed Tsarina protested against the outrage to her womanhood; and when, some years later, a young general, Gleboff, was ordered to inspect the convent, and betrayed some compassion for the deposed Tsarina, she speedily became enamoured of him. He returned her passion, but when rumors of their romance reached the ears of the Emperor, Peter, the most liberal and clever of the Russian sovereigns, promptly had Gleboff impaled upon a wooden stake, while Evdokia, at the instance of the Empress Catherine, was immured in the Fortress of Schluesselburg. There she was kept in a stone tower, known to this day as the “Tsarina’s Bower,” in which she subsequently died.

145

146

Underneath the same “Tsarina’s Bower,” some years later, the Emperor Johann Antonovich passed his joyless days. In the history of mankind there is hardly an instance comparable to the life of that unhappy Emperor. When a baby of only two months he was proclaimed “Tsar of all the Russias”; but less than a year later, in 1740, while still a child at the breast, he was deposed by Elizabeth Petrovna, the daughter of Peter I. She appropriated the crown herself, and exiled the deposed baby Emperor to the polar regions. When he reached the age of four years, the Empress, fearing in him a future avenger, caused him to be confined in a far distant northern prison. But in 1756, when the boy was in his sixteenth year, he was secretly, in the dead of night, carried away from his prison and confined in an underground cell of the Schluesselburg, underneath the tower in which the Tsarina Evdokia had met her tragic fate. The mystery with which his interment in the Schluesselburg was surrounded was so great that even the commandant of the fortress was not supposed to suspect his identity. He was referred to simply as “the said prisoner.” Nobody was allowed to visit him, and his guards were forbidden to speak to him. Only three officers knew who he was, and they had strict orders from the ruling Empress to kill him immediately, should any attempt be made to release him.

After the death of the Empress Elizabeth, Peter III. visited the prisoner in the Schluesselburg, and expressed his intention of liberating him. But Peter’s wife, the future Empress Catherine the Great, soon deposed her husband and prepared for him apartments in the Schluesselburg. He never occupied them, however, for the reason that two of Catherine’s favorites strangled him, in the hope of gaining the good graces of the Empress. This happened on the 17th of July, 1762, and two years later the unhappy Emperor Johann was stabbed to death by his guards during an attempt that was made to release him. So ended the life of this man who had been proclaimed Emperor but had literally never made one step outside his prison walls during the whole of his existence.

The Schluesselburg, however, was not reserved for royalty and persons of exalted rank. Many persons of less importance found a grave within the fortress. As an example I will give the fate of Krugly, who had dared to dissent from the Orthodox Church. He was brought to the Schluesselburg with heavy irons upon his feet and arms. The commandant of the fortress was ordered “to put the prisoner in a cell near which nobody should ever pass, and immediately to brick up the doors and windows of that cell, leaving only one small wicket through which each day a portion of bread and water should be passed; to attach to the cell a strong and watchful guard, and strictly to order those guards that nobody be allowed to approach the little wicket.” The guards were forbidden, under pain of “severest tortures,” to speak to the prisoner in any circumstances or for any reason whatsoever.

Krugly was interred in this “issueless” cell on October 21, 1745. When all the egresses of his cell were blocked, his future in the stone coffin seemed so hideous to Krugly that he resolved to put an end to his life. The only way to do so was by starvation, and Krugly began from the very first day to starve himself. The guards, following their orders, placed the bread and water daily through the wicket; but the prisoner took only the water and left the bread. Thirteen days passed in this manner. On the fourteenth Krugly ceased to take the water. During the following week the guards heard no sound whatever from the prisoner. The little wicket in the thick wall was not large enough to enable them to see into the interior of the cell. At last, on November 12, the commandant of the fortress, Bokhin, reported to the Government that “the chained prisoner takes no bread and no water, and nothing is heard of him.” He therefore asked permission to break through the wall of the cell and to examine the prisoner. Five days later he received the permission. His next report ran as follows:

“Upon investigation, the prisoner was found to be dead. His body has been buried within the fortress.”

The chronicles of the eighteenth century tell us of many other persons incarcerated in the Schluesselburg, among whom was the noble-hearted publisher Novikoff, who was thrown into the fortress and kept there for fifteen years by the “liberal-minded” Catherine II.

The nineteenth century, however, was that in which the Schluesselburg won its fame in Russian history. Not only grown persons but mere children of sixteen and seventeen were cast to rot within its damp, dark cells.

In the cell in which the Emperor Johann had perished, the great Polish patriot, Valerian Lukasinsky, was kept for thirty-seven years.

He was arrested in 1822 for the crime of organizing a Pan-Polish Secret Society, in order to unite the three dissected parts of Poland. Till 1831 he was imprisoned in a Polish fortress, but, as it was known that a certain Grand Duke was also implicated in his plot, it was found expedient for diplomatic reasons to transfer him to

146

147

the Schluesselburg, that “he should be kept there in secret, so that his name and origin should be known to the commandant of the fortress alone.” And the secret was kept so well that in 1850 the Chief of Gendarmes applied to the War Minister for information concerning the identity and crime of that “old Pole lying in the Schluesselburg.”

When the Emperor Alexander II. ascended the throne, a niece of Lukasinsky begged the Tsar to allow her to visit her uncle; but this was refused her. In 1861 the commandant of the Schluesselburg reported to the Emperor that “the seventy-five-year-old Lukasinsky has nearly lost his sight and hearing, and is suffering from gall-stones, but nevertheless is still lying in an underground cell,” and he begged that his lot might be alleviated. Alexander II. permitted him to be placed in a lighter cell, and to take a walk from time to time within the walls of the fortress. But another demand to see him on the part of Lukasinsky’s relatives was again refused. Lukasinsky died in 1868, at the age of eighty-two, after an uninterrupted imprisonment of forty-six years. This is a unique example of a mighty constitution which, reduced to the life of a mole, could resist insanity and death for so long.

In 1869 the Schluesselburg Fortress was discarded as a political prison; but not for long. Fifteen years later a new building with forty cells for political prisoners was built, and a new chapter of horrors was opened in the history of the prison.

This chapter I will set down here as it has been related to me by the few survivors whom the revolution of 1905 released from their living death in the fortress.

II

In the silence of the night of August 2, 1884, a ship of a peculiar and mysterious type was towed by a small steamer to the little landing-stage outside the Fortress SS. Peter and Paul, the Bastille of St. Petersburg. The capital lay motionless, asleep. Only the sentinels on the walls of the fortress paced backward and forward between the cannons which point so grimly across the river at the Palace of the Tsars. On the opposite side of the Neva other sentinels kept vigilant watch upon the vast roofs of the blood-colored Winter Palace. The ship seemed like a connecting link between the two immense buildings. It was gray in color and in shape like a pauper’s coffin. In its wooden sides were several tiny port-holes which, by day, let some meager rays of light into its dark interior. The strong iron gratings fixed across these holes added to the sinister aspect of the vessel.

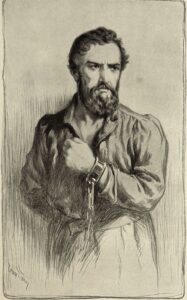

Within the fortress there was an unaccustomed stir, and strange sounds broke the usual deathlike stillness. Soldiers carrying an anvil, instruments, and a heap of chains, headed by Sokolof, the governor of the prison, went from cell to cell and fastened irons upon the feet of the political prisoners.

Another batch of soldiers visited the cells soon after the first had left them; and the prisoners, one after another, were handcuffed also. Shortly afterward, on the same night, the doors of the cells opened once more with their gloomy clang, and the prisoners were taken out of the building and carried away to the mysterious vessel.

When ten prisoners were safe under lock and key, the little steamer, feebly sounding her whistle, moved away, towing the heavy vessel up the current of the Neva. The river was still sleeping, and no other craft were encountered by this silent and mysterious procession. Hour after hour passed away. At last the ship reached its destination. The “Tsar’s Gates” of the Schluesselburg Fortress opened wide, like the jaws of a monster, and swallowed its victims, one after another, most of them forever.

Two nights later the same evil-looking barge was again waiting at the gates of SS. Peter and Paul, and eleven more prisoners were carried away to the Schluesselburg. This first group of twenty-one had been selected as the most dangerous among the Russian political prisoners. From various towns in Russia and from the convict mines in the remotest parts of Siberia they had been concentrated in the Fortress of SS. Peter and Paul, thence to be transferred to the Schluesselburg, in the ship especially constructed for the purpose.

In several cases their journeys back to St. Petersburg from their place of imprisonment or exile had been attended with remarkable incidents. Schedrin, for instance, had been condemned to hard labor in the convict mines of Siberia, and for an attempt to escape from there had been sentenced to be chained to a heavy wheelbarrow. When the order came for his transfer from Siberia to St. Petersburg, no conveyance could be found large enough to contain him, the wheelbarrow, and the convoy of gendarmes. Yet, as the wheelbarrow had become a part of the prisoner, the gendarmes were afraid to leave it behind. It was therefore decided to place Schedrin with his convoy in one cart and the wheelbarrow behind in another. For several months, day and night, Schedrin and the gendarmes galloped through

147

148

Siberia upon a troika (a three-horsed cart or sledge), while another sped behind them, upon which the wheelbarrow reposed—causing the deepest amazement among the peasants in the villages through which they passed. Upon the arrival of the prisoner in SS. Peter and Paul he was once again chained to the barrow, and only after he had been six weeks in the Schluesselburg was he finally detached from it and given freedom of movement within the narrow confines of his cell.

“When they unchained me,” said Schedrin subsequently, “I could not get enough movement. I wanted to run and run, and it seemed to me that I could never stop. How strange it is that men who can enjoy perfect freedom of movement never realize the wonderful happiness that is theirs!”

All the new inmates of the Schluesselburg had previously undergone long terms of imprisonment. Dolgushin, for instance, having been in prison since 1873, had undergone eleven years of imprisonment before being transferred to the Schluesselburg; Myshkin had undergone nine years; Minakov and six others had spent five years in prison; and the remainder from two to three years. The health of all was severely shaken. Some of them were suffering from scurvy or consumption, while others were bordering on insanity. They were the survivors, many of their friends having perished already in the Fortress of SS. Peter and Paul, where they had all been kept for some time, amid terrible conditions, before their removal to the Schluesselburg.

The regime and the aspect of the new prison had been most carefully thought out and planned, being, as the ministers visiting the Schluesselburg repeatedly declared to the prisoners, intended to demonstrate to them that it was destined to be their grave. The cells were constructed in such a manner as constantly to remind the prisoners of a tomb. The stone floors were painted black and the walls dark gray. The window-panes were opaque, so that no ray of sun ever penetrated within the cells, and no trace of color from without could be caught by the prisoners. The iron bedstead was turned up by day and chained against the wall, and only a little stool, also fastened in its place, allowed the prisoners an occasional rest from the incessant stride backward and forward across the floor of the cell.

This pacing back and forth was, in fact, the only diversion permitted to the prisoners. No books were given to them except the Bible, which they had already learned from cover to cover in the Fortress of SS. Peter and Paul; no work for their hands, no color for their eyes, no sound for their ears. Cut off from the living world, buried in the black stone cells, clothed in the dingy prison garb, with one sleeve black, the other yellow, they strode to and fro from corner to corner of their cage. Their food was abominable: bread, half raw, made of rotten flour; and a plate of hot water in which floated a few shreds of meat or the traces of an onion.

At night, when the beds were let down, their racked nerves drove sleep away. Every few minutes their abnormally sharpened hearing distinguished cautious steps in the corridor approaching the door, and the removal of the flap from the spy-glass, through which the hated eye of the gendarme met their fevered gaze. This spy-glass irritated them to a degree incomprehensible to people living under normal conditions. Schedrin, the prisoner of the wheelbarrow, soon became completely insane. He imagined that the gendarmes had made it their object to “sap out his brains,” for which purpose they constantly peeped at him through the spy-glass. Then he began to imagine that one half of his head had already shrunk away, but that the other half and one eye still remained to him, and that he must preserve it at all price by concealing it from the view of the gendarmes.

Schedrin’s terrible shrieks resounded at night throughout the prison, bringing the other prisoners to a state bordering on delirium. The governor of the prison, Sokolov (he was named “Herod” because of his brutality and cruelty), punished the unhappy madman for his cries and insubordination. The guards, rushing into his cell, overpowered him, and, thrusting a gag into his mouth, bound him in a strait-waistcoat upon his bed. For seven years the authorities refused to alter the conditions of his life. And only in 1891, when his madness had turned into apathetic idiocy, did they cease to restrain him. For five years more, however, he was kept in his cell, and only in 1896 was removed to a lunatic asylum.

Life under such conditions became more and more unbearable. Being prevented from speaking, the prisoners endeavored to communicate with one another by raps upon the wall, during the intervals when the spy-glass was covered. They were thus able to interchange a few ideas. But “Herod,” obeying superior orders, strove to preserve the system of absolute isolation, and when a prisoner was caught knocking upon his wall he was treated in the same manner in which Schedrin had been for his disturbances. The slightest noise in the prison resounded with tenfold force because of the absolute stillness,

148

149

and the sound of the ill-treatment of one of the prisoners brought the others to a state of exasperation. To protest against the outrage upon one of their number, they filled the prison with the sound of shrieks and blows upon the doors of their cells. As a result they were, one after another, severely ill-treated, gagged, and bound.

During the first three months of their incarceration many of the prisoners came to the conclusion that they had been reprieved from hanging only to be submitted to a slower and more terrible death. They decided to protest against this by the only means within their power. Immediately after their arrival at the Schluesselburg the regulations of the fortress had been brought to them to read. In these it was set forth that any offense offered to the authorities was punishable by death. Minakov, who had passed five years in a solitary cell before being brought to the Schluesselburg, decided to starve himself unless he were allowed to have books and intercourse with his fellow prisoners. When, after several days of voluntary starvation, his strength gave out, the doctor was brought into his cell to feed him artificially. Minakov struck the doctor, demanding execution according to the regulations. A few days later he was tried by court martial and condemned to death.

It was proposed to him by the governor that he should write an appeal for mercy to the Tsar; but he rejected the proposition. On the day of his execution he asked permission to write a letter to his parents, but permission was refused him. Then the other prisoners heard the measured steps of the convoy in the

149

150

corridor, and they listened to what followed with strained attention. The convoy entered Minakov’s cell, and the voice of “Herod” was heard: “No need for the coat. Give him the cap.” Then Minakov’s voice was raised. “Good-by, brothers,” he cried. “I am going to be shot.” And a few minutes later the sound of a volley in the courtyard reached the ears of the prisoners.

A few days after this another prisoner, Klimenko, hanged himself in his cell, and shortly after, on Christmas day, the prison silence was suddenly broken by the sound of a tin plate dashed against the wall. Then followed the sound of hurried feet, and a loud cry from the famous prisoner, Myshkin:

“I demand execution!”

The listeners were frozen with horror. They understood that Myshkin had thrown his plate at “Herod” in order to be court-martialed.

Myshkin was tried, condemned, and shot.

Myshkin was a man of wonderful eloquence and lofty mind. In 1875 he journeyed to eastern Siberia, disguised as an officer, in order to arrange the escape of the great Russian economist, Chernyshevsky, who had been imprisoned in Siberia since 1863, alone, in a prison especially built for him. Myshkin was recognized, arrested, and brought to St. Petersburg.

After three years of solitary confinement, he was tried, and in his defense pronounced a speech of such force and inspiration, from beginning to end so scathing an indictment against the methods of the Russian Government, that it became famous over all Russia. For this speech he was condemned to ten years’ penal servitude in Siberia. On his way thither, one of his fellow prisoners died, and Myshkin at his funeral made another speech.

“Upon the soil that is fertilized by such blood as thine, beloved comrade,” he said, “will spring up and blossom the tree of Russian Freedom.”

For these words his term was prolonged, by administrative order (without trial), to twenty-five years. He subsequently succeeded in escaping from the convict mines, and safely reached Vladivostok (a distance of two thousand miles), where he hoped to find an English or a Japanese steamer. But the police, who had been warned by wire of his arrival, arrested him and conveyed him back to St. Petersburg for life-long imprisonment in the Schluesselburg. These two speeches were Myshkin’s only crime; and for these crimes a life which would have been glorious in any other country ended in an unknown grave beneath the walls of the Schluesselburg.

150

151

Minakov, who was executed before Myshkin, had an even smaller record of crime than Myshkin. He had wished to teach socialism to the workmen, and, though himself of a rich family, he left the University and entered a factory in Odessa as a simple workman. An agent-provocateur who affected a great friendship for him denounced him, and Minakov was court-martialed and sentenced to ten years’ penal servitude. While in Siberia he joined Myshkin in his attempt to escape, but was caught and sent to the Schluesselburg. He was executed five weeks after his arrival.

I I I

Meanwhile the sinister barge resumed its journeys between the two fortresses. On a cold, bright October night in 1884, the little police-steamer again towed the barge to the landing-stage of SS. Peter and Paul. The unusual stir was again noticeable within the walls of the fortress. The huge oak doors of one of the cells opened, and an old gray-headed guard approached the iron bedstead. He bent down toward the sleeping prisoner with a strange expression of pity and restraint. The prisoner was a young and beautiful woman. She lay beneath the ragged convict blanket upon some coarse sacking, covering some rotten straw, and her loose black curls streamed over a pillow of the same coarse substance. In spite of the cold and the extreme discomfort of her bed, youth had conquered, and the young Ludmilla Volkenstein slept so soundly that the harsh grating of the key in the lock and the footsteps of the approaching guard had not awakened her.

The old man touched her gently on the shoulder, and she started from her sleep, opening her large dark eyes in bewilderment.

“What has happened!” she exclaimed; but, on seeing the old gendarme, the only one of her jailers who treated her kindly, she grew calm.

“Nothing has happened,” he said; “but they are going to take you away from here. You must get up and dress.”

The girl began to tremble with delight.

“Where am I going, Little Grandfather?” she asked him eagerly. She always gave him that name because of his kindly old face and his gentle treatment of her.

151

152

“I don’t know,” he answered. “But get up, and I will bring you some clothes.”

He brought her own underlinen and dress, and left the cell.

“I could hardly see the clothes for my joy,” she says in her reminiscences, which were found twenty-five years later, after her death.

“I was going away . . . my own clothes . . . that meant a journey. . . . To Moscow? . . . To Siberia?

“I was hardly dressed, when a huge sheepskin and a pair of felt top-boots were thrust into my cell. I was so agitated that I could not get my feet into the boots, and the ‘Little Grandfather’ put them on for me. I thanked him warmly for his disinterested kindness. Though the service was small, it meant a great deal to me, because the other guards had all become completely brutalized. When I put on the sheepskin, my arms suddenly disappeared, because the sleeves hung down half a yard below my finger-tips, so the ‘Little Grandfather’ was obliged to fasten the belt around my waist.”

The youthful prisoner felt happy because she hoped that now she would see her mother and her little son again.

Only a few days before this young woman had been condemned to death in the famous trial of fourteen prisoners, of which the central figure had been another woman, also young – Vera Figner. Mme. Volkenstein had never been a revolutionary leader, and in the charges brought against her there was not one that would be considered criminal in any free country. She was accused of being a member of the revolutionary party, “the People’s Will,” and this she proudly admitted, while refusing to defend her case. She was the daughter of a Russian nobleman, and finished her studies brilliantly in Kieff, the central town of poetical Little Russia. The girl had a kind and noble heart, and when sixteen years of age she resolved to devote herself as a nurse to alleviating the sufferings of the peasantry.

She married early a doctor of medicine, who sympathized with her ideas, and they lived together happily with their little son until the police and spies began to make her life and work among the peasants an impossibility. She detested violence of any kind; but after several years of hopeless attempt to help the people by peaceful methods she finally threw in her lot with the party of active struggle against the government, “the People’s Will.”

152

153

153

154

Her husband refused to follow her along this path, and so she was obliged to leave her family. Before many months she was arrested, together with Vera Figner, upon the denunciation of a traitor. The Government, irritated by her proud courage and fearless bearing, ordered the judges to condemn her to death, together with Vera Figner and six men, of whom five were military officers.

During the trial Mme. Volkenstein was allowed to see her mother and her little son, to console the former and to caress the latter. But immediately after the sentence she was taken back to the fortress and clothed in the most loathsome convict rags of the ordinary criminal type. Soap and a comb were refused her, and this impossibility of keeping herself clean and tidy was, she says, to her, a woman, more difficult to bear than the death sentence. But her severest trial was the refusal of a last farewell meeting with her mother and little son.

“Could I only have seen them once more,’’ she says, “to impress the image of my little son more strongly on my heart, and to comfort my dear mother!”

She refused, however, to appeal against the sentence, or to sign the petition for reprieve which was laid before her by the governor of the fortress.

“My death,” she thought, — “the death of a woman, — will serve the cause of freedom.”

A few days later the commandant of the fortress informed her that the death sentence had been commuted to one of fifteen years’ penal servitude, and once more she was filled with the hope of seeing her beloved ones. But, eight hours later, with heavy irons upon her wrists, she was carried in the prison ship to the stone cells of the Schluesselburg, never to see her mother or child again.

Vera Figner was also transferred to the Schluesselburg, and, at about the same time, nine other prisoners

154

155

arrived there. But their conveyance was ways accomplished with such mystery that not one of the prisoners was aware of the identity of the others.

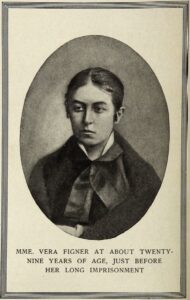

Vera Figner is perhaps the most remarkable of the many heroines of the Russian revolution, In many respects she differed from Mme. Volkenstein. Also of great personal charm, she was slenderly built and hardly of medium height, while Mme. Volkenstein was of robust

155

156

and healthy appearance. Yet this slender, delicate girl was at one time more feared by the Autocrat of all the Russias than any of the Great Powers of Europe. Mme. Volkenstein was strong-minded, but the main features of her character were purely feminine — extreme kindliness, and devotion to the alleviation of human suffering. The predominant feature of Vera Figner’s character is one that is most characteristic of the Anglo-Saxon — doggedness.

“I was always conservative by nature,” she said to me not long ago; “that is to say, I could never change my plans in a hurry. But when once I had come to a decision, I stuck to it till the end.”

Her father, like Mme. Volkenstein’s father, was a nobleman, and a Government inspector of forests. But his estates were situated, not in the mild and seductive surroundings of Little Russia, but in the severer atmosphere of the Kazan Province, in eastern Russia. In this province Vera Figner was born, and already in her childhood her imagination was awakened by the strange stories she heard from the old family nurse about the Russian heroes of olden times, and about her own ancestors. Two of these had been hanged in 1773, during the famous Pugatcheff insurrection, by the riotous insurgents. The wife of one was a Chinese woman, and during the riots she was locked into a cellar by her servants to save her from the insurgents. When the mob had passed on, the servants hastened to unlock the cellar door. They found their mistress dead, just delivered of a little daughter, who was still alive. This little girl was the grandmother of Vera’s mother. Vera’s grandfather took the lead in the guerrilla war of 1812, started by the Russian nation against Napoleon. His patriotism and successful leadership won him fame and the epaulets of a general. Vera’s father was a man of spotless honor, and much respected in the neighborhood for his intellect. But his character was austere, and he held the domestic reins with unbending discipline. From his six children, of whom Vera was the eldest, he demanded absolute veracity, regardless of penalties that it might bring upon them; and this rule was also strictly applied to the mother, who was a mere child of sixteen when she married him, and was powerless to oppose the stronger mind of her husband. But her feeling of protest against his despotic nature united her to her six children, of whom Vera was the eldest.

When Vera reached the age of nineteen she married, but her mind was already filled with

156

157

the idea of helping and enlightening the peasants, who in the province of Kazan are more down-trodden and miserable, perhaps, than in any other part of Russia. Her father died soon after her marriage, and his iron grip was removed from the family. Vera decided to go to Switzerland to study medicine, in order better to be able to pursue her desire of helping the peasantry, and she remained abroad for four years, at the end of that time returning to Russia.

Her first impressions upon her return were not encouraging. Her sister was in prison in Moscow; and almost the whole circle of young people with whom she had studied in Zurich were in prison, in solitary confinement.

Mme. Figner settled among the peasants as a medical help, and endeavored with her medical knowledge to cope with the evils brought upon them By their poverty and ignorance.

“In no other country save Russia would I have been prosecuted for my activity,” she said to the judges at her trial; “in fact, I would have been considered as a not useless member of society. But, as it was, very soon a whole league was formed against me, at the head of which was the Chief of Nobility and the district Chief of Police, while the ranks were filled by such small fry as the village clerk and policeman. All sorts of legends were spread about me: I lived without a passport, my diplomas were forged, etc., etc. When the peasants refused to work for paupers’ wages, it was put down as my fault; when the salary of the village clerk was lowered, I was the cause of the evil. The police invaded the village and several of the peasants were arrested. They began to fear to seek my medical help openly, doing so only by stealth. I began to ask myself, ‘Of what use am I here?’”

She tried to settle in another village, but immediately the impenetrable wall of police and spies arose once more to separate her from the peasants. For over a year she struggled against these obstacles; and only when she learned that her arrest was imminent did she relinquish her plans. She had come to the conclusion that in order that the people might be helped, help itself must be made free, and this could be accomplished only by the destruction of the autocratic regime. Unable any longer to live under her own passport for fear of arrest, she joined the party of “the People’s Will,” and for six years lived under various assumed names. Little by little she came to believe that government by violence can be overcome only by violence, and having once made this decision, she acted upon it till the end.

Without committing acts of violence herself, she nevertheless supported every project of the Party. The Party claimed political and civic liberties, and declared that as long as their members were being hanged or done to slow death in prisons or in Siberia for having tried to teach the people, they considered themselves justified in retaliating upon the head of the despotic Government — “striking at the center,” as their motto was. In spite of all precautions taken by the Government, the Party became so daring, their readiness for self-sacrifice so boundless, that the stronghold of the Tsars seemed shaken to its very foundations. Bridges and railways over which the Tsar was expected to pass were undermined; the very Winter Palace was blown into the air; and at last, on March 13, 1881, the Tsar Alexander II. fell, in broad daylight, in the heart of his capital, surrounded by troops. The Party then expressed their readiness to lay down their arms if the new Tsar, Alexander III., would grant a constitution. He wavered; but his ministers promptly hanged six of the persons accused of regicide, among them being a youth of nineteen and a young girl, Sophie Perovska, herself the daughter of a Minister of the Interior. The execution of another woman, Gesse Gelfman, was postponed because she was expecting to become a mother. As soon as her child was born in the prison, it was taken away from her, and she died of a broken heart. Her husband shot himself.

The war between the Party and the Government was resumed; but this time the balance turned in favor of the Government, and Alexander III. resolutely applied himself to reaction. One by one, the leaders of the Party were arrested and either hanged or sent in exile to the convict mines. Vera Figner alone, always vigilant and resourceful, remained in freedom. She went from town to town, reorganizing the scattered forces of the Party, enlisting numbers of followers by her superior intelligence, eloquence, and invincible charm. Persons of high military and social rank and literary fame, working-men and -women, flocked around Vera Figner wherever she appeared. In all classes she found recruits for the dangerous work of the Party. Her own existence was hedged in by perils, anxieties, and the greatest discomfort. She was constantly being forced to change her name, her appearance, and her passport. And this anxious life lasted for six years, during which she was on the brink of arrest many times, and avoided it only by hairbreadth escapes. She cared little for her personal safety. Her one great object was the reconstruction of the Party. She succeeded in forming a large

157

158

organization of military and naval officers who literally worshiped her. But this in the end brought about a catastrophe. One of their number, named Degaeff, turned traitor, and gave away the whole organization, together with Vera Figner herself.

When Vera Figner had been arrested and lay in the Fortress of SS. Peter and Paul awaiting trial, General Sereda was ordered by the Tsar to investigate her case. When he entered her cell in his gorgeous and imposing uniform, he took the prisoner’s hand and kissed it.

“Vera Nikolaevna,” he said to her, “you are the most beautiful, the noblest, and most courageous of Russian women. If only you had had children and this had never happened!”

Minakov and Klimenko were already dead when the two young women, Vera Nikolaevna Figner and Ludmilla Volkenstein, were brought to the Schluesselburg. Soon after their arrival two of Vera Figner’s friends, the officers Rogacheff and Baron Stromberg, were executed; but she did not learn of this until many years later. Myshkin shared their fate in the manner already related. Several of the prisoners had lost their reason. Tikhanovich and Yuvacheff had become possessed of religious mania, and Aronchik believed himself to be an English “milord.” The rest, seeing nothing but slow death before them, resolved at least to die fighting. They tried to work out a common plan of action, communicating it one to another by the rapping method. No ill-treatment, no strait-waistcoats, could daunt them. At times all the prisoners were bound to their beds, with wooden gags in their mouths. But the rapping was immediately resumed on their release. Then “Herod” invented a novel plan. He ordered the gendarmes to beat upon brass trays in order to drown the sound of the rapping. A competition in the most frightful noise commenced between the prisoners and the gendarmes. The former hammered upon their walls with all their power, while the latter kept up a brazen accompaniment upon their trays. This pandemonium would last for hours at a time, sometimes the whole night through, until both parties were brought to the verge of madness; while “Herod,” with a face of indescribable fury, rushed from cell to cell, shouting:

“I’ll strangle you!”

To which the prisoners responded:

“Go to the devil!”

“Herod” would gladly have hanged them all; but he had received no orders to that effect, and dared not even report the case, for fear of damaging his fair fame as a capable jailer.

The two young women joined in the warfare with “Herod” as dauntlessly as the men. But they had trials of their own which are unknown to men. The constant and absolute exposure to the prying eyes of men was a terrible affliction for them; and every Saturday a new trial awaited them, when “Herod” came into their cells with a woman whose duty it was to search them. These searches were absolutely aimless and exceedingly painful. Nothing could possibly be concealed upon them, because of the constant espionage to which they were subjected. Nevertheless a thorough search of their persons, even to their hair, was regularly carried out. “Herod” watched operations through the spy-glass, and when the prisoners, noticing this, raised a protest, he answered them brutally:

“Have we never seen a naked woman before?”

After a few months of such life not one of the prisoners was in a state of health. Scurvy was prevalent, and many of them became ill with lung-diseases and began to spit blood. Vera Figner described to me the horror she felt when, during her short solitary walks in the courtyard, she saw the traces of this blood upon the snow. The few minutes of exercise in the open air became a torture to her. Her own nerves were so unsettled that the slightest noise caused her to tremble all over, and yet she continued to rap upon her wall to cheer a down-spirited fellow prisoner or to support a general protest against “Herod.”

When the prisoners, one after another, were stricken with disease or madness, it appeared that not the slightest care was to be taken of them, and no hospital was prepared for them. Those who suffered from scurvy, their teeth becoming loosened, were unable to chew hard food. Yet they were given the same coarse rye bread as before; and the consumptives were treated in the same manner.

The two exhausted women lay upon the cold stone floors of their cells, and they, moreover, were more lightly clothed than the men. Mme. Volkenstein became dangerously ill with inflammation of the lungs. Some medicine was prescribed for her by the doctor, but nobody attempted to nurse her, and nobody entered her cell save for the purpose of bringing food or searching her. For weeks she could not move from her bed.

Death haunted the prison perpetually during these first years. The insane Tikhanovich was among the first to succumb. His dying shrieks were frightful. Malevsky, Butzevich, and Nemolovsky died one after another, all from consumption. Dolgushin succumbed from sheer

158

159

exhaustion. When death was near, in order to hide the knowledge of it from the other prisoners, the dying were carried away to an old building called the “stable,” in which the cells were exceedingly damp, dark, and cold. In this appalling solitude they breathed their last.

At the end of 1887 Grachevsky, unable to stand his life any longer, struck a guard in order to be executed. But the commandant of the fortress declared him to be insane and therefore exempt from punishment.

“Then,” said Grachevsky, “it remains for me but to kill myself.” He was taken to the “stable” and kept there under most vigilant watch.

“One night,” related Ludmilla Volkenstein, “a terrible, inhuman shriek was heard. Footsteps hurried toward Grachevsky’s cell. Feeble groans followed, and then his door was quickly opened, and it was evident that something terrible had happened to him. Smoke and the smell of burnt clothing and flesh pervaded the building and hung about it till the following day. We then knew that Grachevsky had burnt himself alive. He had soaked his clothes and bedding with the oil from the little night-lamp, and, rolling himself up in his blanket, had set it on fire. For several days beforehand he had disarmed the suspicions of his guards by exceedingly rational behavior, so that they had relaxed their watchfulness a little and enabled him to commit the dreadful deed.”

IV

This tragedy brought about a new regime in the Schluesselburg. “Herod” was dismissed for having “allowed the prisoner Grachevsky to burn himself.” “Herod” upon his dismissal was seized with a paralytic stroke.

At last it became evident to the authorities that if no change were made in the conditions of the fortress, all the prisoners would soon be dead. Such a contingency was not desirable, it being necessary to uphold the institution in order to preserve the many posts and salaries attached to it. A new governor was appointed, and conditions now became milder. In the courtyard several tiny allotments were given to the prisoners, in which they were at liberty to cultivate flowers and vegetables. Each tiny plot was surrounded by double wooden walls four yards high, and in each two prisoners were free to work. The women were also given a little plot.

“My nerves and constitution,” says Vera Figner, “were shaken to the bottom. I was physically weak, and mentally almost abnormal. And here, suddenly, a friend was given to me; and that friend was the incarnation of tenderness and love. When some calamity had happened in the prison, when our friends lay dying in agony, we met, pale, trembling, and silent. We avoided each other’s eyes, but, embracing each other, we silently walked along the little path, or sat silent side by side upon the ground. On such days the mere physical proximity, the mere possibility of grasping the hand of a friend, was a blissful relief.”

However, even this consolation they were soon forced to relinquish. They learned that it had not been accorded to all of them, and, thinking it unjust to be privileged above the others, they refused the daily meeting.

For a year and a half they endured this voluntary privation, until at last, impelled by more deaths among the prisoners, the authorities gave in, and all the prisoners enjoyed equal privileges and were allowed books to read. But these privileges which they had wrested from the Government at such terrible cost were never stable. In 1889, five years after their imprisonment, after a visit from the Chief of Gendarmes, General Shebeko, the allowance of books was suddenly discontinued. These books were their only instruments of self-forgetfulness, and the prisoners resolved to commence a “famine strike” rather than to lose them. For ten days no food was taken by the prisoners; but as this was ignored by the authorities, they resolved to abandon the “famine strike” in favor of some more effective measure. The strike had hastened the death of several more of the prisoners.

Of the fifty-three persons brought into the Schluesselburg between 1884 and 1889, nine were executed; five went mad; sixteen died or committed suicide; and three were removed to Siberia. Less than half the number survived the first five years, and only in 1890 was a decided improvement made in the conduct of the prison. The isolation from the outer world was as complete as before, but the prisoners were given opportunities of meeting one another, and more books were given to them; little workshops for carpentry, etc., were opened; their gardening plots were extended, and the wooden walls separating them were lowered, so that the sun could shine upon them and the prisoners could see and speak to one another during their work.

This regime lasted for twelve years, till 1902. And in their little forgotten island the prisoners showed of what they would have been capable had their energies been given free play. The little plots were transformed into wonderful plantations. Even tobacco was cultivated in

159

160

them, and the astonished gendarmes beheld the prisoners smoking “real cigarettes.” The most artistic objects in carved wood and iron were turned out in the little workshops, and the prison authorities gladly took possession of them. The breakages in musical and other delicate instruments belonging to the prison authorities were always skilfully repaired in the prison workshops. Most interesting collections of minerals, insects, and plants were arranged by the prisoners. One hundred and fifty of these collections were purchased by one of the St. Petersburg museums through the medium of the prison doctor.

Thanks to the vegetables grown by the prisoners, their food became more varied; and the long hours of work in the open air partially restored health to those who were not beyond hope of restoration. At the same time, through the constant addition of new books to the prison library, the intellectual activity of the prisoners became intense and systematic. There were among them men of high education in science, economics, history, etc., such as Lukashevich, Morosov, and Lopatin. Regular courses of lectures were established, and each prisoner endeavored to develop his store of knowledge to the utmost. This was not because of any hope that, a day of freedom might dawn for them, or that their knowledge might be of use to mankind. It was simply to satisfy the natural craving of the brain. Their days were more or less occupied. “But,” said Colonel Ashenbrenner, “it was not flowers or vegetables or workshops that were necessary to us; what we really needed was — freedom.”

Vera Figner was the natural center of this prison life. She herself took to carpentering, making wardrobes, tables, chairs, binding books, painting on wood, boot-making, and arranging collections. She made, among other things, a tin coffee-pot, and a straw hat which became an object of much pride to the fellow prisoner to whom it was presented. She was a great reader of science, literature, and philosophy. She studied the English and Italian languages in her cell, and translated much of Kipling into Russian. Her love-longing heart also found some outlet. She brought up some orphaned swallows whose nest had been blown down from the prison roofs by the summer storms. The little creatures were intelligent and affectionate. They followed her about in her cell like little dogs, fluttered on to her lap, and frequently in the early summer mornings they nestled upon her breast and awoke her by their chirping. When they grew up she let them fly — herself remaining alone behind the bars of her prison. She was the center of the prison life as, when free, she had been of the revolutionary party.

“Energetic, intrepid, ever ready for self-sacrifice,” says Ashenbrenner of Vera Figner, “she was always to the fore, and no wonder that in great as well as in small matters all eyes instinctively turned toward her, awaiting a word, a sign, an example.”

She had frequently been incarcerated in the dreaded “black hole” for six days at a time, with no food save dry bread and water, and no resting-place but the damp stone floor. But this had never bowed her dauntless spirit. And she had had other bitter griefs with which she had fought alone and uncomplaining.

In 1888 Uri Bogdanovich, the dearest friend of her life, who for so many years had fought side by side with her in the revolutionary struggle, lay dying of consumption in the third cell from her own. When, a month before his death, the General of Gendarmes visited the cells, she, for the first and only time, stooped to ask a favor of her jailers. She asked that she might be transferred to a cell next to that of her dying friend, so that she could speak to him at least through the dividing wall, and that his last moments might not be so utterly lone and friendless. Bogdanovich joined her in this petition, but it was refused. She could hear his dying moans, but could not soothe them, and she knew that he died alone and unattended. His death was such a bitter sorrow to her that for several months afterward she shut herself up in her cell, refusing to leave it even for exercise, and beseeching her fellow prisoners to leave her in peace and not to endeavor to communicate with her. When at last she emerged from her cell and joined in the prison life once more, no trace could be seen of her terrible and lonely struggle.

In 1896 the companion of Vera Figner’s walks, Ludmilla Volkenstein, finished her term in the Schluesselburg and was transferred to the island of Sakhalin; there she was immediately joined, after fifteen years’ separation, by her husband.

Vera Figner thus lost the only person with whom she was allowed freely to consort. The men could meet one another, but Vera Figner was kept apart from them. She could hear their voices, but could not see them. She worked alone, in her little garden, in her workshop, in her cell. Only some years later was she allowed to see her fellow prisoners through the little wicket in the door of her workshop.

In this way eighteen years of prison life passed away. A few of the prisoners at the end of their terms were transferred to places

160

161

of exile. Janovich was sent to eastern Siberia, but the contact with the outer world was overwhelming to his shattered nerves, and he shot himself. Martynof, also transferred to Siberia, shot himself for the same reason. Polivanov, in 1902, after twenty years of imprisonment was exiled to Central Asia. He escaped from there and went to Switzerland. There he met Aseff, the traitor of hideous fame, who persuaded him to return to Russia with a bomb, and even accompanied him to the shores of Bretagne to test its explosive force. On his way to Russia, Polivanov stopped in a French town, and shot himself, leaving a note which ran:

“No strength is left in me to live.”

A few weeks before Polivanov’s release from the Schluesselburg, a new change had taken place in the prison regime. The revolutionary movement in Russia had grown very powerful, and in order to suppress it such towers of reaction as Sipiagin, and after his assassination Plehve, had been placed at the head of the Government. Plehve ordered many of the privileges won during the previous years by the prisoners of the Schluesselburg to be denied them. But those few who survived after twenty years felt that a return to the old order of things would be worse than death to them.

Vera Figner, without informing her friends, decided to die for them. When the governor of the fortress entered her cell, she, by a sudden unexpected movement, tore the epaulets from his shoulders and flung them in his face. She expected to be court-martialed and shot for this action, but believed that it would at the same time restore to her friends their former privileges. When the other prisoners learned of what had happened, they immediately informed the governor that if Vera Figner were touched they would all imitate her action, and die, by one means or another.

For this reason, or because of other considerations, Vera Figner was left unpunished. And, more than that, by a curious stroke of fate, it even turned to her advantage. Her mother somehow learned of the danger that threatened her daughter. During their last meeting, in 1884, on the day of Vera’s condemnation to death, she had extracted from her mother a promise that she would never ask a favor from the Government for the purpose of bettering her daughter’s lot. For eighteen years the mother kept this promise; but when news of this new danger reached her, she could resist no longer. She appealed to the Tsar — her son is one of the greatest Russian singers and the chief singer of the Court. The Tsar ordered that Vera’s sentence should be reduced from life-long imprisonment to detention for twenty years. Eighteen years had passed since her trial, but she had been kept two years in prison awaiting trial. The mother therefore hoped for her daughter’s immediate release; but Plehve ordained that it should be otherwise.

“There is still too much life left in her,’’ he said, and ordered that she should remain two years longer in the Schluesselburg.

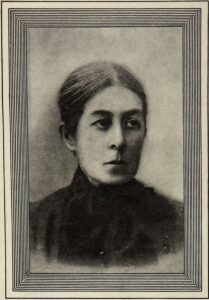

The mother, in the meantime, became incurably ill, and counted the days that brought her nearer to her child. But not before the full term had elapsed was Vera Figner released. It was too late. Her mother’s death had occurred a few weeks before. To this day, Mme. Figner cannot speak of her mother without a burst of tears.

Several months ago, four years after her release, I was walking with Mme. Vera Figner in London. After a few minutes’ walk she was so tired that she was obliged to take my arm. She was telling me of her impressions since her release from the Schluesselburg.

“When I think,’’ she said, “of those past long years, it seems to me as though they were a nightmare. To be here now, in this great city; to be free and to watch the whirl of life . . . I often ask myself, Is it really I? Am I not dreaming still? Am I really living?’’

A heavy cart suddenly rumbled by. Mme. Figner let go my arm and, pressing her hands to her ears, began to tremble all over.

“ It was the sudden noise,’’ she said in explanation, still very pale. “ But I am gradually getting stronger. At first I could not bear the slightest noise.”

Mme. Figner was not set free immediately after her release from the Schluesselburg. She was first kept in the Fortress SS. Peter and Paul for a month, and afterward transferred to another prison in the town of Archangel in the most northern part of Russia, where she remained for another month.

“You see,” she said ironically, “the authorities considered that a sudden great change might be bad for me. But the delays were exceedingly exhausting.”

At last she was sent to her place of exile, a tiny village close to the polar regions.

“They considered me a very valuable piece of State property,” she said, “and took the greatest precautions. First the police were sent in advance to examine the whole stretch of the river Pinega, to see if the ice were strong enough to bear me. Only when they returned with a satisfactory report, was our procession

161

162

allowed to start. Our avant-garde was formed by a three-horsed sledge drawing the Chief of Police himself. Then came another troika, occupied by me and my sister, who had joined me in exile. Behind us came the sledges of the convoy. We caused the greatest sensation wherever we passed, and a legend spread among the population that the Grand Duchess Elizabeth Feodorovna had fallen into disfavor with the Tsar, and was being carried to exile. When in the Archangel prison, I frequently corresponded with the Princess Korsakova, and perhaps my letters addressed to ‘Her Highness’ gave birth to this rumor.

“‘The little Duchess is going about asking the peasants how they live,’ said the people. ‘She writes it all down in a little book, and she is going to ask the Tsar to help them.’

“When I was brought to the village that was to be my place of exile, this story caused me great discomfort, as the peasants constantly besieged me with requests for help and all sorts of complaints. From far distant villages came letters with various demands.

“Only after I had spent nine months in this village was I allowed to settle on our Kazan estate,” she said. “When I took the steamer at Ribinsk and saw the Volga again, I felt for the first time that I was free. We passed through the scenery which I knew so well and for which I had longed for a quarter of a century. But still, even now, I was not left in peace. Two police officers in plain clothes, especially selected for their loyalty, were fastened upon me, and I was obliged to pay their passage and even to make them a daily allowance.

“The authorities said to my sister, ‘We know she won’t run away, but the Party may abduct her by force in order to have her in their hands.’ ”

When at last Vera Figner arrived on the family estate she was the mere shadow of a human being. She suffered from insomnia, and the slightest sound at night, even the fall of a button in the quiet country house, caused her to shriek aloud, terrifying all its inmates. When her brother, the great court singer, Figner, at her request began to sing to her, she burst into tears and hurried from the room. Her relations constantly feared that she might commit suicide.

“The first year and a half,” she said, “it was very difficult for me to live in freedom. I had no desire to live at all. I was like a plant suddenly uprooted from the ground and left to wither in the air. The appetite for life had left me, and I could find no object in living. I felt no desire to overcome obstacles, or to clear a path in life for myself. And, note, the others felt the same after leaving the Schluesselburg. Even Lukashevich, the powerful giant, only forty years of age, told me that he felt the same, and Surovsteff told me that he desired to enter a monastery in order to get away from life. Ludmilla Volkenstein said that her feelings were the same.”

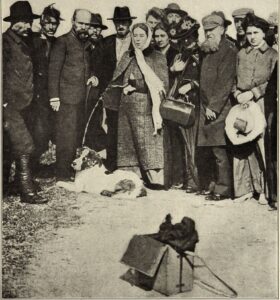

Poor Ludmilla Volkenstein! She was put out of her sufferings by the benevolent authorities. After having passed through thirteen years in the Schluesselburg, she was sent to the convict island of Sakhalin, and there she spent another seven years, living, as she wrote in her letters, in conditions of “indescribable horror.” Only in 1904 was she allowed to remove to the continent of Asia. She wished to settle in the town of Vladivostok, but the commandant of the fortress of that town refused to allow it, and proposed that she should settle in some uninhabitable corner of the Amur wilderness. But the cholera broke out just then in Vladivostok, and there were not enough doctors to cope with it. Mme. Volkenstein’s husband, who was a doctor, was asked to remain in Vladivostok, and he agreed to do so on condition that his wife remain with him. For a year they worked together side by side, tending the invalided soldiers and the population. Then came the time of revolution. On January 10, 1906, the commandant of the fortress having arrested the doctor most popular among the soldiers, Lankovsky, a deputation headed by the military governor of the town went through the streets to the commandant to ask for the doctor’s release. Mme. Volkenstein was one of the deputation. When it turned the corner of one of the streets, it was met by a volley of bullets from the fortress. Forty persons were killed on the spot, and among them fell Ludmilla Volkenstein, pierced by several bullets. It was a great and noble heart that ceased to beat — the heart of a woman whose whole life had been one long self-sacrifice.

But her leader, Vera Figner, is still with us. She was at last allowed to go to Italy for a cure. Here freedom, the southern climate, the beauty of nature, and the tenderness of her friends wrought a miracle. Vera Figner is again active, filled with a desire to live in order to help the innumerable victims of Tsardom in the Russian prisons and in exile. Quite unexpectedly, she has developed an unusual gift of oratory, which is the more impressive because of her extraordinary self-restraint, simplicity, and modesty. She is now addressing crowded meetings all over Great Britain. Her nervous system is still extremely delicate, and she frequently returns home nearly prostrated by the excitement of those meetings; but her indomitable

162

163

will and determination overcome physical weakness.

One of the Schluesselburg prisoners, Nicholas Morosov, had always retained a strange, never-failing belief that their release was near. He had been condemned to penal servitude, and had been in the prison ever since 1881. Every winter he assured his fellow prisoners that the next spring they would be released; and when the spring passed, he again assured them that release would come next autumn; and so on, from year to year, for twenty-five years. In October, 1905, while he was taking his exercise in the yard with another prisoner, the gendarme suddenly summoned them to the commandant.

“What can he want us for?” asked Morosov’s companion.

“Why, to release us, of course,” said Morosov, with conviction.

And this time he was right. A few days before, a revolution in the form of a general strike had broken out in Russia. The gates of the Schluesselburg opened and set free the remaining eight prisoners.*

Beneath the walls of the Schluesselburg, on the narrow strip of land touching the water, there are eight and twenty graves of the Schluesselburg prisoners. In the dead of night the gendarmes had dug them, and had covered them with green turf, hoping to hide all trace of them forever. But Nature has frustrated this design. In the course of years the graves have sunk below the surrounding level, and twenty-eight green indentations mark the spot where the Martyrs of the Schluesselburg lie sleeping.

—

* The political prison in Schluesselburg was emptied in 1905, and thrown open for public inspection. It was announced that the career of this most terrible of bastilles was at an end. But a year later, after the triumph of reaction, the emptied cells were re-peopled, and now they are filled to overflowing. The eight veteran prisoners who were released by the amnesty have been replaced by three hundred prisoners, political and criminal, and these are crowded together in conditions that defy description.

ETERNAL Spirit of the chainless Mind—

Brightest in dungeons, Liberty, thou art!

For there thy habitation is the heart —

The heart which love of thee alone can bind;

And when thy sons to fetters are consigned,—

To fetters, and the damp vault’s dayless gloom,—

Their country conquers with their martyrdom.

And Freedom’s fame finds wings on every wind.

From Byron’s Sonnet on Bonnivard

163