I. P. Youvatshev (Iuvachev), The Russian Bastille, or the Schluesselburg Fortress

TНЕ RUSSIAN BASTILLE

OR THE SCHLUESSELBURG FORTRESS BY I. P. YOUVATSHEV

TRANSLATED FROM THE RUSSIAN BY DR. A. S. RAPPOPORT

ILLUSTRATED BY 16 PICTURES AND PUBLISHED AT LONDON BY CHATTO & WINDUS MCMIX

THIS BOOK IS DEDICATED TO THE MEMORY OF THE BEAUTIFUL SOPHIA GINSBURG, WHO COMMITTED SUICIDE IN THE CASEMATES OF SCHLUESSELBURG, IN ORDER TO ESCAPE A FATE WHICH EVERY NOBLE WOMAN FEARS MORE THAN DEATH.

A. S. R.

vii

TRANSLATOR’S PREFACE

‘Had I been told in my childhood,’ says the author of the present book, I. P. Youvatshev, ‘that one day people would lock me up in a narrow cage, deprive me of sunshine and air, and keep me there for years, I should never have believed it.’ And yet the day did come when he was torn away from those most dear to him, and condemned to solitary confinement, in which he struggled hard not to lose his reason. So great were his sufferings that when he was at last sent to Sakhalin among criminals and assassins, he greeted this exile as a joyful occurrence and a happy deliverance. For was he not going once more to behold the sky, the sun and the stars, and, what was more, to hear the sound of human voices — the voices of criminals and outcasts, but human voices after all?

Ivan Pavlovitsh Youvatshev was born in 1860. After passing his preliminary examinations he entered the Naval Technical Institute, which he left in 1878, and subsequently served as an officer in the Black Sea Fleet. Being of a serious dis-

vii

viii

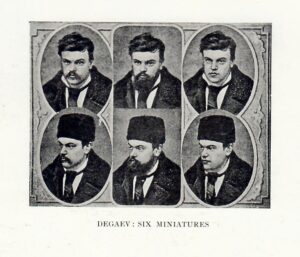

position and finding no pleasure in the ordinary occupations of his colleagues, such as card-playing, drinking, and flirting, he worked very assiduously and read a great deal on political and scientific subjects. It was natural, therefore, for him to develop a keen interest in the sufferings of the Russian nation, and to manifest sympathy with all liberal measures intended to ameliorate the fate of the oppressed millions. Youvatshev was thus one of the ‘thinking’ officers of the Russian Navy. But ‘to think’ is a crime even in so-called Constitutional Russia of 1909; it was much more so in 1882-83. The famous Degaev, who had turned spy in the pay of the Secret Police, had, at that period, handed over a list of all those officers who were regarded by the revolutionary party as ‘thinking’ young men to the head of the Secret Police, and many arrests were the result of this act of treachery. Among the arrested was also the author of the present book; he was taken to the fortress of St. Peter and St. Paul on August 13, 1883. Although there was practically nothing to prove his revolutionary tendencies, he was tried as the organizer of a naval military circle and condemned to death. The sentence was afterwards commuted to one of penal servitude in the mines for an unlimited period. Before, however, Youvatshev and his

viii

ix

fellow-sufferers were sent to Sakhalin they had to undergo a term of solitary confinement in the living tombs of Schluesselburg. Many lost their reason, many others escaped the agony of suffering by courting death; Youvatshev himself was in frequent fear of going mad. How he succeeded in keeping his mental balance he relates in the thrilling pages of the present work. In 1886 he was informed that the authorities had decided to transfer him to Sakhalin, where he would undergo a term of fifteen years’ penal servitude. Some time before his departure for Sakhalin he was visited in his cell by the Assistant Home Secretary. The latter, on being informed that Youvatshev was preparing a new translation of the Gospels from the Greek, and believing that the prisoner was religiously inclined, advised him to become a monk — by which step he would be able to escape penal servitude.

‘I have no inclination for a monastic life,’ replied the prisoner.

‘But I am anxious to assist you,’ said the high official, ‘and am therefore offering you the only means which will make you free. You have no other hope.’

‘I place my hope in God alone,’ replied Ivan Pavlovitsh.

The Cabinet Minister shrugged his shoulders and left him to his fate.

ix

x

On leaving Schluesselburg, Youvatshev was detained for some time in the casemates of the fortress of St. Peter and St. Paul, and only in 1887, four years after the day of his arrest, did he reach Sakhalin.

The life on the island was by no means a pleasant one, but it was not to be compared with the existence in the living tomb of Schluesselburg, On Sakhalin he was again allowed to enjoy the sunshine, to breathe the fragrant air of fields and forests, to communicate his thoughts to other men — in a word, to feel himself again a human being, a privilege which was denied to him during his confinement in Schluesselburg. In virtue of the Imperial Manifesto of 1891, his term of servitude was reduced to one-third, and in 1895 he left Sakhalin for Vladivostock, where he was engaged in the construction of a railway in the capacity of technical engineer. In 1897 he was allowed to return to Russia, where he found his aged parents still alive. In 1899 he was reinstated in his civil rights, and has since then devoted his time and labour to literary activity and research, publishing a number of books and articles, among them the present reminiscences. Youvatshev is thus one of the few who were fortunate enough to escape death and madness in Schluesselburg and afterwards in the mines. From the living tombs of the Russian

x

xi

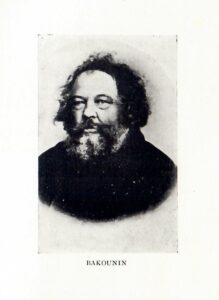

Bastille he returned to life and even happiness. But how many have been swallowed up by the Moloch Autocracy and cut off in the prime of life! How many a noble existence has been crushed in those living tombs where Russian Autocracy is constantly flinging her best and noblest citizens, whose only crime may be summed up in the one word — Thought. Russia’s Poets and Prophets, Russia’s Thinkers and Philosophers, Russia’s Bakounins,* Hertzens, and Kropotkins, have either suffered this fate, or are in constant danger of being visited by it. The words, ‘Woe unto the nations who stone their prophets!’ may rightly be applied in modern times to the Russians. The fate of our author and of his fellow-prisoners mentioned in his reminiscences calls to our mind the names of many Russian Authors and Poets, many Thinkers, who have perished since the noble family of Romanov has been presiding over the destinies of the nation.

If not exactly stoned, the Russian Poets and Authors — the Prophets of modern times — have met with sufferings and premature death. They have either been hanged or have been sent to Siberian mines among the lowest and worst

—

* Michael Bakounin was detained for eight years in the fortress of St. Peter and St. Paul, and then exiled to Siberia — whence he escaped.

xi

xii

criminals. ‘The history of Russian thinkers,’ Alexander Herzen once exclaimed, ‘is a long list of martyrs and a register of convicts.’ A terrible destiny awaits in Russia those who dare to step beyond the line traced by the hand of the Government, or who venture to look over the wall erected by Imperial Ukase. In the most civilized countries of Western Europe ever and anon a cross-current of reaction traverses the stream of intellectual evolution: narrow-minded zealots, hypocritical bigots, false prophets and literary Gibeonites, gossiping old women arrayed in the mantles of philosophers, do their best to put fetters on the independent thought of man, to nip free intellectual development in the very bud, and crush it under the iron heel of tradition and authority. These reactionary tendencies, however, are only exceptions in Western Europe. Not so in Russia. There, the Thinkers whose life the paternal Imperial Government spares die in the prime of youth, before they have had time to develop; they wither like blossoms hurrying to quit life before they could bear fruit. Their number is legion, but I shall mention at least a few of the names of Russian Authors whose glorious talent and melancholy fate add to the ignominy of Russia’s history, and who, if not hanged, were, like Youvatshev, either confined in the fortress or sent to the mines, but were not

xii

xiii

so lucky as our author in being able to return to life and activity.

Nicolai Ivanovitsh Novikov (1744-1818), journalist and philanthropist, who had devoted his life and his property to the welfare of his nation, endeavouring to raise its low intellectual level by founding schools and libraries, was arrested in 1792 by order of Catherine IT., the friend of Diderot and Voltaire, and confined in the fortress at Schluesselburg.

Ryleev (1795-1826), a poet of considerable talent, was hanged with four others in 1826 by order of Tsar Nicholas I.

Prince Odoievsky (1802-39), whose poems are full of poignancy and pathos, was sent to Siberia, where he had to pass his life as a common soldier. His is not the only case where the Russian Government, by way of punishing authors for their daring words, forces them into the military service. The army seems to be considered by the Government of the Northern Empire as a kind of convict prison.

Griboyedov, Russia’s Beaumarchais (1794-1829), the famous author of the comedy ‘Gore ot Oomah,’ or ‘Too much Intelligence comes to Grief,’ met with so many obstacles in his literary activity, and was so disgusted with the intellectual and moral state of Russia, that he was haunted by constant thoughts of suicide. He sought refuge in Persia, where he was murdered.

xiii

xiv

The promising poet and philosopher Wenewitinov (1805-27) died in his twenty-third year, a victim of social circumstances.

The fiery poet Alexander Polezhaev (1810-38) attracted the attention of Nicholas I. by his satirical poem ‘Sashka,’ which was secretly circulated among his schoolfellows. The poet was expelled from the University and sent as a common soldier to serve in a Caucasian regiment. The soldier-poet sought oblivion of his wretched life in drink, and finally died in a military hospital at the age of twenty-eight. The manner in which Polezhaev was treated by the Tsar is very characteristic of the Romanovs, who commit all their atrocities in a spirit of clemency.

Nicholas I. ordered Polezhaev to appear before him and to read the poem. The Tsar then kissed the student on the forehead, in appreciation of his talents, and afterwards ordered his enlistment in a regiment. This was evidently done with a view to breaking the independent spirit of the poet and to crushing the rising genius by cutting his wings. But this cruel joke is not the only one in which the Imperial Government of Russia indulges from time to time.

In 1836 Tshaadaev, the friend of Schelling, and author of ‘L’Apologie d’un Fou,’ published a letter in French in which, Prometheus-like, he cast his curse into the face of Russia. He told

xiv

xv

her, in clear and precise words, that her past was useless, her present superfluous, and her future hopeless. Tshaadaev’s letter was a trumpet-call by which he wished to rouse Russia from her sleep of inertia. But his voice was soon silenced. The Government did not punish him, but — by order of the Tsar — Tshaadaev was declared mad.

Bestuzhev (Mariinsky, 1795-1837), the founder of Romantic Criticism in Russia, was sent to the mines for a few years and died in the Caucasus.

Tshernyshevsky, who has been somewhat rashly styled the Russian Robespierre, but who could more correctly be compared with John Stuart Mill, created a sensation with his novel ‘What shall we do?’ (1863), and was consequently torn away from his literary activity and sent to Siberia.

Byelinsky (1810-48), the Russian Lessing, the famous literary critic, who exercised an immense influence upon Russian literature, died of privation in his thirty-eighth year. Where the Government does not condemn the talented men to a life of misery, to degradation and death, it puts so many obstacles in their way that they are driven to despair, and die young and wretched, victims of oppression, crushed under the iron heel of tyranny. The famous Russian novelist Dostoievsky, the eminent psychologist who, with critical scalpel in hand, analyzed the Russian soul and laid bare its most hidden cells, was sent to

xvi

xvi

Siberia for four years, where he lived among thieves and murderers. Afterwards he served as a soldier in a Siberian regiment. And how many are there — their name is legion — who have been crushed before they had had time to raise their voice! Few have sufficient strength to hide their emotions and the burning fire of enthusiasm in the innermost depths of their soul, without being consumed by the inward flame. Few indeed are those who, with fetters on hands and feet, succeed in keeping their heads erect and their spirits independent. The great Russian poet Pushkin, liberty-thirsting and revolutionary, was exiled to the Caucasus. He returned home, but soon again had to choose between a second exile or the title and uniform of Imperial Chamberlain. He chose the latter alternative.

‘In this lack of pride and power of resistance,’ says Herzen, ‘the defect of the Russian character manifests itself.’

If Tolstoi has been spared, it is not because the Government is afraid of European opinion and does not dare to touch him, but because the author of ‘Resurrection’ is absolutely harmless. The Government, on the contrary, avails itself of his doctrine of passive resistance, of castration of the will and submission, for its own purposes. Not so Gorky. If his head has been saved till now, there is no guarantee that he will not one

xvii

xvii

day share the fate of his glorious predecessors.

Gorky preaches the Gospel of Independence, and is dangerous to the autocratic Government.

He must therefore beware. Such is the fate of Russia’s Prophets, Poets, Philosophers, and Thinkers. And the vast millions look on, apathetically and stupidly, while the best and most talented among them are crushed, while the few ‘intellectuals,’ of whom Russia ought to be proud, disappear prematurely for the sake of a few dissolute and brainless individuals.

From time to time the Russian nation, like a child, raises a cry, but soon, like a child again, it subsides, kisses the rod that punishes it, and cries itself to sleep, under the influence of the whisperings of mystic superstition and the vapours of vodka. And meanwhile the work of destruction continues its course. The fathomless abyss is swallowing up the best and most talented before they have time to exercise their power. Is the nation free from blame? We doubt it. If the nation at large does not directly stone its prophets, their fate is on its head nevertheless, for its passive attitude is the cause of their destruction.

‘Woe,’ therefore we repeat, ‘unto the nation that stones its prophets!’

A. S. R.

April 1909.

xvii

CONTENTS

CHAPTER PAGE

INTRODUCTORY 1

I. THE TRIAL 3

II. PUT IN FETTERS 11

III. IN SCHLUESSELBURG 18

IV. THE PRISON DIRECTOR 25

V. NEIGHBOURS IN SUFFERING 30

VI. THE FIRST DAY IN THE NEW CELL 36

VII. DESPAIR 43

VIII. FAILING EYESIGHT 51

IX. THE PHANTOM OF INSANITY 57

X. A NEW FRIEND 62

XI. COURTING DEATH 69

XII. SUICIDE OF GRATSHEVSKY 74

XIII. VISITING OFFICIALS 80

XIV. SASHKA THE ENGINEER 86

XV. MONEY THE MAINSTAY OF THE REVOLUTION 95

XVI. A MOTHER’S LAST BLESSING 101

XVII. EASTER GREETINGS 106

XVIII. THE BLUE SKY AGAIN 112

XIX. SAKHALIN 120

XX. THE DEPARTURE OF THE LAST PRISONERS 125

XXI. TWENTY YEARS IN A LIVING TOMB 132

xix

xx

CONTENTS

CHAPTER PAGE

XXII. A VISIT TO THE RUSSIAN BASTILLE 138

XXIII. THE INMATES OF THE BASTILLE 148

XXIV. THE INMATES OF THE BASTILLE (CONTINUED) 160

XXV. THE EMPEROR IVAN ANTONOVITSH 169

XXVI. POLITICAL CRIMINALS IN THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY 182

XXVII. THE CITADEL 193

XXVIII. A MOTHER OF THE PRISONERS 204

XXIX. A BREACH IN THE PRISON WALLS 211

XXX. THE PRAYERS OF THE MARTYRS 218

GLOSSARY 223

xx

xxi

ILLUSTRATIONS TO FACE PAGE

EMPEROR PETER III. VISITING IVAN VI. IN HIS CELL IN SCHLUESSELBURG Frontispiece

DEGAEV: SIX MINIATURES viii

BAKOUNIN xi

VERA NICOLAEVNA FIGNER 18

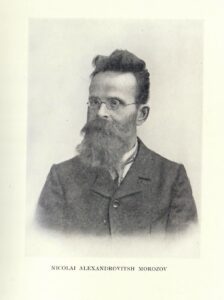

NICOLAI ALEXANDROVITSH MOROZOV 65

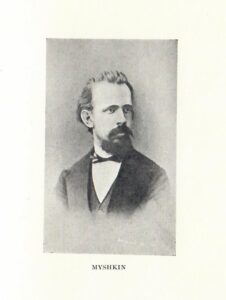

I. N. MYSHKIN 72

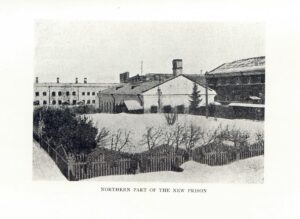

NORTHERN PART OF THE NEW PRISON 75

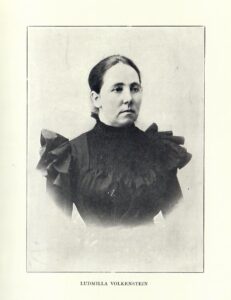

LUDMILLA WOLKENSTEIN 102

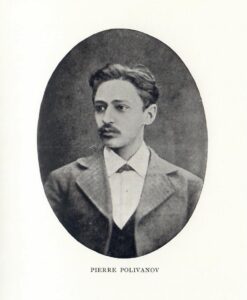

PIERRE POLIVANOV 106

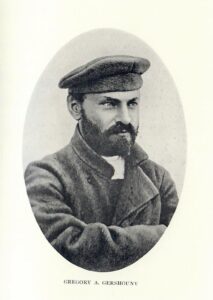

GREGORY A. GERSHOUNY 126

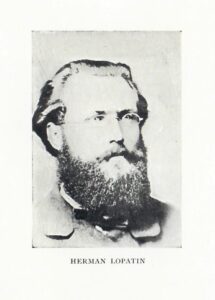

LOPATIN 128

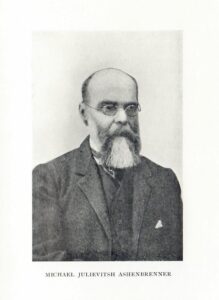

MICHAEL JULIEVITSH ASHENBRENNER 132

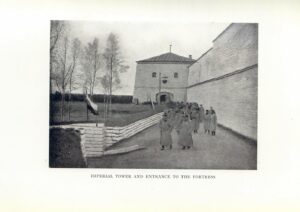

IMPERIAL TOWER AND ENTRANCE TO THE FORTRESS 140

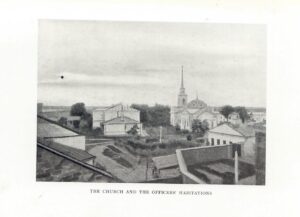

THE CHURCH AND THE OFFICERS’ HABITATIONS 143

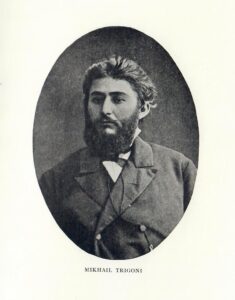

MIKHAIL TRIGONY 150

PRINCESS MARIA MIKHAILOVNA DONDOUKOVA-KORSAKOVA 204

xxi

THE RUSSIAN BASTILLE

1

THE RUSSIAN BASTILLE

INTRODUCTORY

‘There were no stars, no earth, no time,

No check, no change, no good, no crime,

But silence, and a stirless breath

Which neither was of life nor death.’

The Prisoner of Chillon.

In the autumn of 1883, about a month after my arrest, during my solitary confinement in the fortress of St. Peter and St. Paul, I received a visit from my sister. The interview took place in a special room, separated in the middle by two gratings running parallel at a distance of about two arsheen from each other. We entered this room through two separate doors and stood at the small aperture made in the gratings, between which sat a prison inspector of tall stature and dressed in a military uniform.

After the first words of greeting and tears, my sister said:

‘I cannot imagine what you can find to do

1

2

within these four wails. How can you exist in this tomb?’

‘I can tell you—–’ I began.

‘You are not allowed to talk about it,’ the inspector curtly interrupted me.

My sister shot a glance at him and burst into tears.

More than one decade has now elapsed since that interview; I have been detained in the meantime in the more terrible fortress of Schluesselburg, I have worked in the mines, and have sojourned on the island of Sakhalin. This was followed by a number of years during which I slowly returned home from exile. At the present moment my solitary confinement has become a distant recollection. But some terrible situations in which I have found myself are still so vividly present to my mind that, without needing to draw on my imagination, I am going to try to give briefly a reply to the question how people can exist in tombs.

2

I THE TRIAL

‘Such is the idea of Christianity which, consciously or unconsciously, has been instilled into all of us from our very cradle, that the prisoner is filled with joy at the thought that the moment of his trial has arrived. The depth of his love and his strength of character are to be tested as a fighter for those ideal benefits which it has been his endeavour to obtain, not for himself, but for the people, for society, and for future generations.’ —

V. N. Figner.

It was the evening of October 1, 1884, The President of the military tribunal at St, Petersburg was reading the final sentence of the court.

From among the fourteen criminals accused of political crimes, eight were sentenced to death. Each case was summed up separately. My turn arrived. I, hearing that I was being accused of having entertained relations with the political criminals, with the naval officer Boutzevitsh and Vera Philippovna Figner, stood as if petrified. Never had I set eyes either on Boutzevitsh or on Vera Figner; never had I even seen their photographs or had any relations with them.

My only acquaintance among the accused

3

4

officers, M. Y. Ashenbrenner, who sat on the first bench, turned round to me, smiling sadly. In reply I only shrugged my shoulders. The President went on mentioning the fact of my belonging to a secret society, and of my having made one of the circle of officers of the Black Sea Fleet. But to this accusation I paid no attention. Could it be considered a crime that we young officers came together in the evening, and, behind the samovar, talked over the latest events in Russia, perhaps with a little more freedom than one is wont to find in the daily press? Did not the officer of gendarmes who accompanied me through St. Petersburg tell me in confidence that he greatly sympathized with the liberal movement? Did not even the assistant Public Prosecutor, under whose supervision our case was conducted, admit that he, too, was counted, during his University days, among the ‘red ones’?

And even the judges themselves must evidently have considered my offence a very small one, if they found it necessary to add the very insignificant transgression of my acquaintanceship with political criminals. I was convinced that they had committed this mistake quite unconsciously. The examining magistrate, the Major of gendarmes, knew quite well that I had never met Vera Figner, and it was he himself who first

4

5

made me acquainted with her biography. The judges, unable to read all the documents relating to my case, decided that I must have been acquainted with Vera Figner and Boutzevitsh, since both once visited the town of Nikolaev, where the naval officers used to stay in the winter. After the final judgment has been read the accused has no right to address the court, and thus I had no opportunity of proving that this time I had been condemned unjustly.

I do not exactly remember the speech of the military Public Prosecutor, but it left upon me the impression that he was expressing his regret at having to accuse me, and acknowledged that he lacked sufficient data to enable him to demand capital punishment in my case.

As for the first Public Prosecutor, I remember that he brought me one day from the fortress of St. Peter and St. Paul into the gendarmerie, facing the church of St. Panteleymon, and addressed me as follows:

‘As far as your comrades are concerned, I have already decided upon the course of my action, but I cannot as yet make up my mind what to do with you.’

I looked him straight in the eyes.

‘You hesitate,’ I thought; ‘you doubt whether you ought to hand me over to a military court, which means capital punishment, or have me

5

6

tried by a civil court, which would send me into some remote province like Archangelsk. Feeling that I am in your power, you take pleasure in playing with me like a cat with a mouse. What is it you want? — that I should implore your mercy and humble myself before you?’

I turned my head away.

And he, who had boasted to me that at my age he, too, had belonged to the ‘red ones,’ decided that I ought to be handed over to a military court. Another detail: we were tried as if we were religious criminals.

‘You are Stundists.’

‘No; we are Baptists,’ replied the accused.

‘No; you are Stundists,’ insisted the court.

‘You will allow us to know best; we are ready to confess.’

And before the military court:

‘You belong to the party of “Popular Freedom.”’

‘No; we belong to a special military organization which has nothing in common with the terroristic tendencies of that party.’

‘No; you belong to the party of “Popular Freedom,”’ insisted the court.

The naval Lieutenant, Baron Stromberg, wished to explain the significance of our military organization, and began by comparing it with that of the Decembrists of 1825. He was not, however,

6

7

allowed to proceed, and was finally sentenced to death. We were led back to our respective cells. Two gendarmes accompanied each criminal, and we had to be very careful on the stairs, so as not to be hit by the sword of the gendarme preceding us. Some of the criminals exchanged a few short sentences. Especial animation was manifested by those who had been condemned to penal servitude. The quick punishment on the scaffold had been commuted for them into a slow one, to be dragged out over a number of years. They hoped to meet somewhere in Siberia. Poor things! They little suspected that slow death awaited them in the living tombs of Schluesselburg. Only a few of them eventually left the fortress alive.

My brother and sister did not long delay coming to see me. They knew that I had been sentenced to death, but, nevertheless, they endeavoured, amid their tears, to convince me that I would not be executed.

‘You have taken no part in assassinations, or even in attempts at any. Why should they kill you?’

I told them that I had been accused of acquaintanceship with persons whom I had never known or seen.

‘And you are silent!’ exclaimed my sister in astonishment. ‘Why don’t you protest?’

7

8

My brother supported her, and advised me to complain against the sentence of the court.

‘Leave me some Socratic consolation,’ I replied.

‘What consolation?’

‘Don’t you remember that when Socrates took the poisoned cup one of his disciples exclaimed, “You are dying innocent!” “Would you prefer to know that I am dying guilty?” replied Socrates. Allow me, too, to enjoy the consolation of knowing that I have been sentenced unjustly.’

The next day I was transferred to the Troubetzky bastion in the fortress of St. Peter and St. Paul, where I had been detained previous to my trial. The place was the same, but the conditions were changed. My naval uniform was taken from me, and I was not allowed the linen and the blue gown from a military hospital which are granted to those still under trial. I was now clad in rough, thick linen, grey trousers and vest, and a round prisoner’s cap. Instead of meat at dinner I now received kasha (gruel), and instead of tea hot water. All this was done in order to make us feel the difference in our situation before and after the trial. A few days of agonized uncertainty succeeded the announcement of our sentence. The important question, ‘To be or not to be,’ had not yet been

8

9

decided. ‘If they find it necessary,’ I thought to myself, ‘to put me to death, then they ought to punish hundreds, thousands, hundreds of thousands of people in Russia. No; they cannot do it.’

I felt a little more hopeful, almost convinced that I should only be exiled to Siberia. I was ready to go to the end of the world. One can live anywhere, only not in solitary confinement.

On Saturday evening, October 6, whilst listening to the chiming of the bells from the churches of the capital and pondering over human fate, I suddenly heard a noise as if of the opening and shutting of doors and of many approaching footsteps. ‘Somebody going the round of the cells,’ I thought. ‘Who can it be? The noise came nearer and nearer. I stood in the middle of my cell, anxiously waiting. They reach my door. It is opened.

A General!

‘A messenger from the Tsar!’ was the thought that flitted across my brain.

The Lieutenant-General, a grey, stout gentleman of tall stature with shoulder-knots, approached me, briefly asking:

‘A naval officer?’

‘Yes, a naval officer,’ I replied.

‘His Imperial Majesty has graciously commuted your sentence of capital punishment to

9

10

that of penal servitude in the mines for fifteen years,’ said the old man, and he laid his hand feelingly on my shoulder.

He sighed heavily, coughed, made an expressive gesture with his hand, his face showing evident compassion, and then, without another word, he left the cell, accompanied by the soldiers and the prison director.

So at last I am relieved from the burden of my suspense. When shall I be sent away?

10

II PUT IN FETTERS

‘During the moments which immediately follow upon his sentence, the mind of the condemned in many respects resembles that of a man on the point of death. Quiet, and as if inspired, he no longer clings to what he is about to leave, but firmly looks in front of him, fully conscious of the fact that what is coming is inevitable.’

V. N. Figner.

A day, two, three pass. No change. Had they forgotten us? Are they waiting for the spring? Uncertainty is often full of torment. What was happening all this while outside my cell? Some of the prisoners have perhaps already been put to death. When and in what manner should we be transported to distant regions? I was completely in the dark. As personalities we were being absolutely ignored. We had become as chattels or as cattle, which are not asked into which stable they would wish to be placed, or with what food they would prefer to be fed. A presentiment as of something horrible about to happen took possession of me.

The night of October 10 arrived. I could not

11

12

sleep. I lay on the bed dressed, and suddenly jumped up and walked across the cell. At last I undressed and went to bed, but no sleep would come. Silence reigned in the prison. The cell, with one little window under the roof, and lit by a lamp, offered no point on which the eye could rest awhile. I turned my face towards the door, and watched the small aperture in it, wondering whether the eye of the jailer would appear through it. But no change even there. I rose again, and went to the iron cask fixed in the wall, to drink some water. I turned on the tap, but only a dark yellow, muddy liquid flowed from it for my refreshment.

Suddenly I heard a noise as of hasty steps along the prison corridor, then as of the opening of prison doors. I listened attentively. A minute afterwards I again heard the noise of footsteps and the dragging of slippers.

Somebody has been taken away.

Whither? For what reason? And at what hour of the night? It must be about one or two after midnight.

Silence again. I lay down. Only the noise of the wind outside could be heard. Suddenly a repetition of the sound of hasty steps and of doors being opened, but this time much nearer.

Some one else has been taken away.

12

13

What did it signify?

My brain began to work. I began making all kinds of impossible guesses.

The footsteps were now approaching my cell. The door was hastily opened, and two soldiers entered. One of them threw me my slippers and prisoner’s gown.

‘Throw the gown over your shoulders and put the slippers on your naked feet, and come with us.’

I obeyed. We descended the stairs into the courtyard of the bastion, where we usually walked about for recreation. It was pitch-dark. I could scarcely distinguish the path leading to a small-sized building in the middle of the courtyard. It was the bath-room.

I felt as if something was squeezing my heart. Why was I being led at such an hour into the baths? Why into this completely isolated building — isolated from the prison and any habitation? And why was I dragged in such cold weather from my bed, clad only in my linen and a thin gown over my shoulders?

The gendarme opened the door, and I stood like one turned to stone by the spectacle which presented itself to me under the strong light of the lamp. On the floor stood an anvil and hammers; chains and other instruments were lying about. Two peasants in red shirts, their sleeves tucked up, produced the impression upon

13

14

me of public executioners. In a corner stood the tall figure of the prison director. The first thought that flashed across my brain was the torture-chamber, the public executioner, torture.

‘Sit down on the floor,’ commanded the prison director. I had scarcely sat down when my naked foot was seized, and the peasants began to pull it with the iron instrument.

‘They are putting me in shackles,’ I guessed, and my first fear of torture disappeared. But it was torture, after all. Only with difficulty could I bear the pain when they placed my foot on the anvil and began to rivet the fetters with the hammer — i.e., to flatten the rivet on the iron ring. Every stroke on the iron sent a vibration of pain through the whole body. ‘What a barbarous method,’ I thought, full of indignation, ‘to beat the thick iron with the sharp edges on a human foot! Could one not invent something more humane and delicate than this thick iron?’ To judge from the workmanship, these fetters must have dated from the time of Peter the Great, if not from earlier still. I recalled a Russian proverb: ‘God gave a free world, but the devil forged its chains.’

At last my feet were iron-clad. I had never before seen and never could have imagined the arrangement and construction of these fetters, nor the method whereby they were forged on the

14

15

foot, although I had often been reminded of them by the students’ song:

‘Let us drink to him

Who drags his shackles,

Who, deprived of freedom,

Is now in the mines.’

Now I, too, might be counted among those of the order of prisoners suffering for an ideal. There are many orders in the world. There are chains to put round the neck; there is an order of the garter. But if anywhere, it is on the fetters of our prisoners that the famous motto Honi soit qui mal у pense ought to be engraved. Trousers of a grey cloth which I had never seen before were now brought. The speciality of these trousers consisted in their having buttons in the place of seams, so as to enable the prisoner to put them on over his fetters. I was dressed in a vest, in peasant’s shoes, with a sheepskin pelisse, a prisoner’s gown, and a grey cap without a visor. I was evidently to be sent off on a long journey — I guessed whither. A leather strap was attached to the middle of the shackles and put in my hand, so as to prevent the chains from trailing on the ground. They began clanking, however, as I was being led back to the exit from the bastion.

‘Pull the leather strap and keep your chains from clanking,’ ordered the prison director.

What secrecy there is about everything in

15

16

the prison! Dragging my legs with difficulty, clad as they were in their unaccustomed garb, I entered the guard-room, and sat down between two gendarmes of gigantic stature. The director had disappeared. I sat for about an hour in this state of suspense. The gendarmes seemed greatly bored. They were continually yawning and stretching themselves. To judge from their dialect and their stature, they were Little Russians. It would be difficult to find another such pair of tall, thick-set, healthy men. The skin on their cheeks seemed to be so tightly stretched that at any moment it might burst. The prison director suddenly reappeared, accompanied by an officer of gendarmes and two jailers carrying a bundle of the clothes in which I had been arrested.

The bundle was undone, and the clothes handed over to the gendarmes, each piece being verified according to the list.

As he was counting the money in my purse» the director suddenly noticed a small paper packet. He carefully opened it. It contained a powder of a darkish colour.

‘What is this?’ he asked me significantly.

I was at first surprised to see this packet in my purse, but suddenly remembered that I often carried with me two or three powders of Kali hуpermаnganicum to clean my teeth.

16

17

‘Oh, I think it must be a powder of manganese of potassium,’ I replied; and, wishing to convince him, I wetted my finger and put it in the powder, to see whether it would produce the characteristic colour. But the director hastily seized my finger and began to wipe it carefully. He evidently suspected poison.

17

III IN SCHLUESSELBURG

‘Jesus Christ did not protest when He was carried off and His face struck. The mere thought of it even is a profanation of His pure personality and mild greatness.’

V. N. Figner.

I was led to the gate, where a carriage was awaiting us. The officer sat down by my side, the two gendarmes opposite. As far as I could guess, it was about four o’clock. It was dark, and the blinds were down.

My brain was still busy, trying to guess where I was going. It was not worth while asking my companions; they would not have answered.

Two or three minutes had scarcely elapsed when the carriage suddenly stopped. Why so soon? The two giants jumped out, and, paying their respects to a General who was expecting us, seized me under the arms. A cold, damp air was wafted against my face.

‘The Neva,’ I guessed in the darkness. ‘What! Are they taking me to the Schluesselburg fortress?’ My soul froze within me. What I had most dreaded was going to happen.

18

19

A small Government steamer (the Moyka or the Fontanka, or another of that kind) was waiting at the landing-place of the fortress of St. Peter and St. Paul. I knew the spot, having often visited it. The blockheads of gendarmes literally dragged me over the landing-place and along the steamer until we reached the cabin at the stern.

The iron rings of my fetters had eaten themselves into my flesh, causing me grievous pain, and I hastened to sit down on the sofa.

In the hurry of taking me away, they had omitted to put on me the fetter protectors, which are made of skin and protect the leg from the rubbing of the iron. This fact, too, was a sure sign that my journey was not to be a long one. But why put us in thick irons at all? I tried to stretch my leg, and the ring of the chain fell down on my ankle. It struck me that only a slight effort was required to take the chain off altogether, and the presence of the gendarmes alone prevented me from trying to do so. The torment caused by putting on the chains was, therefore, only a matter of form, serving no purpose whatever in a case of emergency. The officer of gendarmes, a Captain by rank, now came down into the cabin, and the steamer at once put off. I looked through the porthole. The town was still asleep. Some-

19

20

where in the distance there were lamps still alight. I had no longer any doubts about my destination. They were taking me to Schluesselburg.

This was indeed unjust. My soul cried out in its indignation. The General had informed me that the Emperor had graciously commuted my sentence to that of penal servitude, and now they were going to take me into solitary confinement. They ought to have asked my consent. They had no right to act without it. The gendarmes brought down a samovar and tea-service, rolls and butter.

‘Please eat,’ the officer invited me.

‘Where are you taking me?’ I asked. ‘To Schluesselburg?’

The Captain spread out his hands and shrugged his shoulders, indicating by this gesture that he could say nothing. But at tea he very minutely spoke of himself and of his sympathies. He laid stress upon the fact that he was a genuine Russian, a man of Moscow, who loved everything that came from that town to such a degree that he even ordered his rolls from Moscow. He hated the new northern capital.

‘Then why are you staying in St. Petersburg?’

‘Moscow is the place to live in, and St. Petersburg to serve in,’ he replied. ‘There is more

20

21

order kept there, and people are not so negligent about their duties as in Moscow.’

As he absented himself several times, and also gave various orders to the gendarmes, I understood that more prisoners, destined for detention in Schluesselburg, were in the fore-cabin.

The day dawned. The weather was damp. Through the dim window I could see the banks of the Neva. Only a year ago I had been enjoying myself in a villa on the ‘Islands.’

We passed the old oak of Peter the Great, and I knew that Schluesselburg was near. Again the forest was seen stretching on both sides of the Neva. The church of the cemetery on the Preobraghensky hill came in sight. A little lower there was a large factory, and behind it the town. The fortress was on the island in front, but I could not see it through the cabin window. The engine stopped, and the steamer approached the landing-place. I had scarcely shown my head above the cabin stairs through the hatchway when the gendarmes seized me and pulled me on deck. I caught sight of a naval officer and sailors. From the steamer I was quickly dragged on shore, where a group of gendarmes and officers were standing. My feet scarcely touched the ground. I was hauled further along the high wall of the fortress until we reached the gate of the tower known as the Imperial. All

21

22

this while my chains were hanging, and the iron rings cutting with their sharp edges into my flesh. The pain was almost unbearable. I was incapable of thinking either of the interior of the fortress, of the church and the tomb, or of the officers’ quarters.

The gendarmes, evidently realizing how I suffered, accelerated their pace, and began almost running. Why all this haste? In order to unload the steamer as quickly as possible and leave the officers at leisure? We entered the iron gates of the prison, which was surrounded by a red stone wall, and I was put down on my legs.

Thank God! I hardly think I could have stood another minute of such severe torture.

The jailers now quickly approached, and began to break away the bolts of my shackles with a pointed tool — a new torture. The heavy strokes of the hammer made my whole body quiver with pain. One of the officers, noticing the expression of agony on my face at every blow, ordered one of the gendarmes to hold the ring with his hands. I felt an immediate and immense relief. The relief was even greater when the iron chains fell off my feet. The joy at feeling free of them even drowned, for a moment, the bitter consciousness that I was entering a living tomb for an indefinite period of time.

22

23

Passing the guard-room, we entered that part of the prison which had only recently been constructed, and had just been inaugurated by receiving the first transport of prisoners from the fortress of St. Peter and St. Paul (August 3, 1884). On entering the prison one is struck by the peculiar construction of its interior. Both stories of the building contain about forty cells, the doors of which all lead into one common space in the middle of the building, as into one high hall, reaching from ground to roof, with windows at both ends. So wherever the jailer stands he can at once overlook all the forty cells. Along the upper story runs a narrow balcony, accessible by a winding iron staircase. In order to prevent any attempt on the part of the prisoners to throw themselves over, a closely woven net is stretched along the upper part of the railing.

I had scarcely had time to look round when I was led into one of the rooms. A group of officers and gendarmes were assembled there, evidently the Commission for the reception of prisoners.

Then my body was subjected to a disgraceful and humiliating examination. I was undressed, and the gendarmes poked their dirty fingers anywhere and everywhere — into my hair, into the secret places of the body, into my mouth. I felt horribly ashamed and hurt. What a savage,

23

24

rude, and disgusting institution! I recall nothing more humiliating during the whole of my sojourn in various prisons.

I was surprised at the indifference with which the officers and the physician witnessed this moral torture. How could they so quietly look on at such a revolting offence to human feelings?

This over, I was again dressed in ungainly grey trousers and a vest of the same kind with black sleeves and a black patch on the back. I thought of the girl of Dostoevsky, who expressed herself concerning the prisoner’s garb in the following words: ‘Ouf! how ugly! and they seem to have run short of grey cloth, too!’ Two gendarmes, one in front and one behind, took me to one of the cells on the upper story. Without words, they very roughly pushed me into it with their hands.

24

IV THE PRISON DIRECTOR

‘It is suffocating under the low, dirty roof;

My strength grows weaker year by year:

They oppress me, this stony floor,

This iron-chained table.

This bedstead, this chair, chained

To the walls, like boards of the grave.

In this eternal, dumb, deep silence

One can only consider oneself a corpse.’

N. A. Morozov.

Before leaving the fortress of St. Peter and St. Paul, I had already decided upon the line of conduct I would adopt towards my jailers. To make violent protestations meant to engage in an unequal fight with these rough, uneducated men, and to provoke them to even crueller insults. An attitude of rebellion on the part of the prisoner, maintained with any insistence, usually led to his violent death, of which many examples existed. I decided that rather than enter upon a struggle in which I was sure to be defeated, it would be better to place myself on a height unattainable by the jailers. I made up my mind to have as little communication with them

25

26

as possible: never to ask anything of them, to enter into no conversation with them, to answer them briefly, and only when it was absolutely necessary; never to oppose or protest, to bear everything in silence, and, above all, never to complain to them. Looking back upon that time, I am convinced that such an attitude was the only means to guard myself from further humiliations and violence on the part of the gendarmes.

I was taken into cell No. 23, the fourth from the end, situated in the south-eastern corner of the building.

After the casemates of the fortress of St. Peter and St. Paul, the cell appeared very small. A little iron table, an iron stool chained to the wall, an iron bedstead turned up against the opposite wall and securely fastened to it, a closet, and a shell-shaped basin with a tap, constituted the entire furniture of my cell. The window, with its thick, dark glass, was almost under the very roof, so that it was scarcely possible to reach even the steeply sloping window-sill. Against the wall in one corner was a small wooden icon of the Virgin Mother, and a little lower, in a more conspicuous place, was a printed declaration from the prison director, informing the prisoner that any attempt on his part to insult the jailers would bring capital punishment in its wake. The

26

27

posting up of these printed words, the only ones the prisoner has to read in a solitary cell, showed an utter ignorance of the human soul on the part of the authorities. These printed lines, constantly before the eyes of the prisoner, gradually set his brain working without intermission on one and the same subject, so that in the end the hypnotized prisoner often threw himself either on the prison director or the prison doctor, demanding capital punishment ‘in accordance with the law.’ In many prisons abroad this mental process has long ago been observed, and such printed posters have been replaced by large placards containing passages from the New Testament.

The director, an elderly Captain of gendarmes, addressed me in the following words: ‘I am obliged to address every prisoner with “thou”; the law ordains it. Please, therefore, not to feel offended when I say “thou.” And thus, dost thou wish to eat?’

I cast a glance at the director’s Hebrew type of face, read in it his past, his list of services, and at once understood everything. And to understand everything, people say, means to forgive everything.

I understood that before me, upright as if on duty, stood a soldier in an officer’s uniform. He looked fifty years old. To judge from the

27

28

St. George’s Cross on his breast, he had been to the wars. He had perhaps subdued the Poles in the insurrection of 18G3. He had evidently afterwards been incorporated in the regiment of gendarmes, had shown his zeal and ardour in service, obeying the commands of his superiors to the letter, never deviating to the right or to the left. No doubt he was often ordered to make many arrests, risking his own life, in acknowledgment of which he had been raised to the rank of officer and appointed director of a political prison. He most probably still continued to execute all the orders of the authorities as minutely and as faithfully as before. The authorities relied on him as on a stone wall; they had faith in his incorruptibility, and in recompense for his services had created him Captain.

Could I feel offended by such a man? Full of the consciousness of performing his duty, he was, in his own mind, trying his very best to deserve the attention of his superiors. What were the prisoners to him? — Mere pieces of wood, without voices, without feelings, and without wishes. Like the centurion in the Gospel, he could boast: ‘I have only to command a prisoner to go, and he will go; to stand still, and he will stand still; to undress, and he will undress; to lie down, and he will lie down. What I command the prisoner must do. Like convicts

28

29

in penal servitude, they are deprived of all rights. If I usually address my subalterns with “ thou,” surely my tongue would disobey me if I even wished to say “you” to my prisoners!’

And how much mischief has this ‘thou’ caused within the walls of Schluesselburg prison!

It was a gross mistake on the part of the Government to appoint an uneducated soldier-gendarme to be the official guardian of a group of ‘intellectuals,’ many of them endowed with fiery natures, and with nerves shattered by the abnormal conditions of their life. Could one expect a soldier like this, intent on obeying the commands of the law to the letter, to understand the psychological state of his prisoners, or to make a study of their particular idiosyncrasies? And there was as much variety in their characters as in those of human beings outside a prison wall. Moreover, it was impossible to apply a strict discipline in the case of people who were ready to sacrifice their lives for the idea of deliverance from oppression of every kind.

The Government, however, seems to have at last understood its mistake, as four years later it removed this ideally obedient servant. It is easy to dismiss a prison director and appoint another in his place, but, unfortunately, the prisoners who have perished under his rule can never be brought to life again.

29

V NEIGHBOURS IN SUFFERING

‘Whoever you are, my sad neighbour,

I love you as a friend of my youth,

Though only my incidental colleague,

Though by the play of cruel fate

We are for ever separated from each other

By a wall now and by mystery later.’

Lermontov.

I was left alone in my cell. The heavy oaken, iron-lined door was shut noisily upon me. The lock snapped. The small cell, 5 feet long and 4 feet wide, suddenly appeared smaller and narrower still.

In the door there was the well-known aperture or casement window, which could be shut, and through which the food was handed in, and above it the ‘eyehole,’ as large as a two-copeck piece, through which the prisoner could be constantly watched.

It was a new place, yet it seemed old and familiar to me. There were the same ceiling, the same cold floor, the same walls. The only difference consisted in the changed condition under

30

31

which I now found myself. In the prison of St. Peter and St, Paul, before my trial, I had received a few rare visits from my relatives, and could hope that I would soon leave my cell and again look upon God’s world—the green fields, forests, and waters—whilst now, isolated as I was from the whole world, there was nothing left to me but the prospect of being buried alive for a few years—‘to abandon everything and forget everything.’

Outside my door heavy steps resounded on the stone floor. The gendarmes who had brought me were evidently leaving the place. The exit was through an iron door, composed of a massive grating, as I had just noticed when I entered the prison. It fell back with a loud noise. They were gone. Everything became suddenly silent. There it was again, the terrible silence of the tomb.

I sat down on the iron footstool chained to the wall, and began to listen for any noises that might come from the outside. No sound penetrated through the window with its double frames, and where, indeed, should any sounds come from, considering that in front of the prison ran an immensely high, thick wall, behind which only the ‘sea roared’? All I could hear from time to time on the farther side of the door was the faint noise of the squeaking of the jailer’s boots as he

31

32

stealthily approached my cell. I began to watch the hole in the door, through which the eye of the jailer was continually reappearing.

And here was again a remarkable combination. Although I was in this close confinement, passing the days in unbroken and painful solitude, yet I was never left to myself. I could do absolutely nothing without a witness; I was all the time in the company of an unknown gendarme, whose watchful eye was constantly tormenting and haunting me. I had to behave, consequently, as the whole world were watching me. I resolved, if therefore, to follow out a programme of conduct which was novel to me—to act in such a manner that I should have no occasion to blush for my transgressions before anyone. Living in society, one is often obliged to make compromises with one’s conscience; but here, in solitary confinement, there was no necessity to adapt oneself to the requirements of social life and to the character of other people; reason and feeling could therefore act freely.

I rose with the intention of walking about, when I suddenly heard a stealthy knock coming from the next cell, whilst at the same time the eye of the jailer appeared in the aperture of the door.

‘Here is a new trial,’ I thought. The director of the prison had informed me that it was strictly

32

33

forbidden to communicate with my neighbours by means of knocks, and that the prisoners caught in the act of knocking were punished severely: and now I was called upon to answer. What was I to do? — Deceive the jailer, and answer my neighbour stealthily? But I had just made up my mind to act in such a manner that I should not have to blush for my transgressions. Should I humiliate myself on account of these soldiers, and lower myself to deceit and shamming? In my first prison I had in the beginning communicated with my neighbour by means of knocks, but I finally abandoned such a method of intercourse. I remember it happened thus: My right-hand neighbour called me, employing a very primitive way of conveying his words. He expressed the letter a by one knock, b by two knocks, the thirtieth letter by thirty knocks, and so on.* Such a method was sufficient to make a nervous individual lose all desire to enter into conversation. But we nevertheless did manage to communicate with one another. I soon learned that my right-hand neighbour was a young man quite unknown to me, but he was greatly interested in my left-hand neighbour, and the two made me their go-between. During our conversations the jailer often penetrated into my cell, made insulting observations, and uttered various threats.

—

* The Russian alphabet has thirty-five letters.

33

34

To avoid all this, I had to knock at the walls in a stealthy manner, like a thief, watching for the moment when the jailer was not near my door, and the moment the noise of his stealthily approaching step was heard rush away from the wall and start walking up and down the cell, putting on an innocent expression of face. Such manoeuvres were for me the source of an indescribable moral torture. It was intensified by my right-hand neighbour. He never asked a simple question, but prefaced it with introductory words, as, for instance: ‘Will you be so good?’ and, ‘Kindly ask your neighbour,’ etc. I used to wait and wait until he had finished his polite preludes, whilst he, as if purposely, was introducing letters of twenty or thirty knocks.* ‘Excuse me, please, I shall trouble you again to ask your neighbour,’ etc., he would say.

My patience often gave way, and all the while I was being tormented by the jailer’s eye and his stealthy footsteps. It is true, my left-hand neighbour did not worry me with such long phrases. On the contrary, he taught me a simpler, commonly adopted system of communication; but he had a remarkable gift of constantly communicating the most incredible and

—

* I.e. words containing such letters as ‘ou’ and ‘ye’ — the twentieth and thirtieth letters of the Russian alphabet.

34

35

horrifying news, and thus not a little helped to shatter my nerves. After such an experience, I had no intention whatever of conversing by means of knocks with my neighbours for my own benefit. But perhaps my neighbour stood in need of it? He was perhaps suffering from his solitary confinement, and yearning to hear at least two or three words from a human being. Should I not help a sufferer who was perhaps on the verge of madness? Did not the young man who had troubled me with his long phrases go mad only three weeks later? I meditated long over the matter, uncertain how to settle the question. To quarrel with the jailers, to deceive them, to lie and sham, was so degrading to me, and such a burden upon my conscience! ‘No,’ I said; ‘I shall wait a little longer before I answer my neighbour, and see how necessary I am to him.’

My neighbour, however, did not insist. I soon heard him knocking against the wall of another cell.

35

VI THE FIRST DAY IN THE NEW CELL

‘Naked walls, prison thoughts,

How dark and sad you are!

How heavy to lie a prisoner inactive,

And dream of years of freedom!’

N. A. Morozov.

And thus I voluntarily condemned myself to unalleviated solitude. I hoped, however, that here, too, books, my faithful friends, would appear.

‘I shall wait a few days,’ I thought, ‘and if the prison director does not think of it himself, then I shall ask him to lend me a book. Oh, how hard it is to ask for anything here!’

I shall never forget how, in the first prison, I had to ask several times for some book, until at last, with a jesuitic smile, I was given a soiled copy of the New Testament, and for some time afterwards my jailers curiously watched me through the eyehole to see what impression this dirty little book, many pages of which were missing, would produce upon me.

After many rebuffs, I at last decided to ask, as far as possible, for nothing—to suffer in silence,

36

37

to wait, and never complain. Whether I felt cold or suffered hunger, or the soles of my boots were trodden out, I remained silent. Such an attitude on my part soon proved to be the best I could have adopted towards my insolent jailers. They became more attentive, even polite, and found out for themselves what I needed. At first they used to find fault with me for the merest trifles. If they noticed, for instance, the slightest scratch on the whitewashed wall — one which they themselves had perhaps casually made — I was immediately overwhelmed with questions and remarks of the most insulting character.

In the new prison, however, a new order of things existed. Here the director kept the prison keys in his own possession. Whenever tea, dinner, or supper was distributed, whenever a medical inspection took place, or the prisoners were taken out for a walk or led to the baths — in every instance the director always opened and locked the doors himself, and the soldiers accompanying him, being under the eye of their officer, were thus prevented from overstepping the bounds of humanity. Some prisoners chose a different line of conduct towards their jailers. They set themselves in determined opposition to them, contradicted them, demanded and insisted upon things, and, at the same time, endeavoured to shield themselves by all possible

37

38

means against insults and impertinences. This often led to encounters exceedingly humiliating for the prisoners. It is possible that, by behaving in this way, the prisoners helped to break the monotony of their lives: it enabled them to play a part in a small drama, and thus gave them a sense of still fighting — i.e., of still living, and not being morally dead. But personally I preferred to look on in silence upon all these prison trifles, bearing them magnanimously with all the physical and moral powers at my disposal. I preferred to arm myself, Christ-like, with a divine silence and an imperturbable patience. It is true that it was somewhat difficult at first to play the magnanimous towards the jailers, but I was rewarded by the comparative peace and tranquillity of soul which I afterwards enjoyed.

I passed the first day in walking to and fro across my cell, reflecting upon the limits of human thought. It is remarkable that the numerous recent impressions produced upon me by my trial, which lasted a week, by the interviews with my relatives, and my transfer from one prison to another, seemed as if suddenly wiped out. I did not even care to try and recall them, whilst my brain was ready to occupy itself with absolutely abstract subjects. Eighteen months had passed since I had been torn away from my family and friends. At first I had been

38

39

able to think of nothing but them. Gradually, however, it seemed as if they had passed into some Nirvana, and a fog of forgetfulness appeared to envelop all my previous life. The more I freed myself from reminiscences, the more my intellect thirsted for new ideas. Never in my life, neither before nor after my confinement, have I noticed in myself such a faculty for reflection as while in prison. It is very possible that brain and heart work the more intensely the less occupation the body finds. In any case, I am compelled to admit that in solitary confinement the intellect seems to free itself from its shackles.

I had been taught in my childhood that one of the characteristics of the animal is its ability to migrate from one place to another. I was now deprived of this freedom. In this sense I was no animal — or, at least, to a very limited degree — my opportunities for migration being confined to a space of 20 square arsheen.* But if, on the one hand, the prisoner is deprived of the freedom of movement and space, on the other he has time at his disposal. But what is the use of time in prison? Would it not be better to forget its existence, to be unconscious of it? Unfortunately, however, the prisoner is not allowed to forget it. As if of set purpose to

—

* A measure of length, an ell, a yard; 1 arsheen = 2 feet 4’242 inches.

39

40

remind him of it, every hour, every half-hour, and even every quarter of an hour, makes itself intrusively known cither by the striking of the clocks or the changing of the sentries. People are accustomed to measure time in various ways, but the unfortunate prisoner measures it chiefly by the stages of his suffering. He does not pass his time in prison: he suffers his time, just as people suffer something disagreeable, something tedious and heavy.

Bedtime came. The soldiers hastily entered my cell, unfastened the bedstead, and pulled it from the wall. It was already made up for the night, and I hastened to get into it. . . . I do not know whether it was the light of the lamp, or whether my nerves had been overwrought by my transfer from one prison to another, or whether I was experiencing the truth of the dictum that one does not sleep in a new place— in any case, I could find no sleep for some time. I listened involuntarily for the stealthy approach of the sentry, and watched for his eye at the hole. I soon, however, grew tired of that, and, shutting my eyes, I began, in the hope of fatiguing my brain, to count how many days and hours I had passed since the moment of my arrest. At last I fell into a doze. ‘A-a-a-ah!’ A loud, prolonged cry of horror resounded through the prison. My hair stood on end; I trembled

40

41

as if shaken by fever. The cry was succeeded by an oppressive silence. Even the sound of the sentry’s step had ceased. Evidently one of the prisoners had been suffering from nightmare, I had often heard similar cries in my first prison, but never did they echo so loudly and hideously as here.

I wrapt myself still closer in my bed-clothes, but could find no rest. Sleep had gone from me entirely. The cry continued to ring in my ears, conjuring up before my mind’s eye pictures, one more terrible than the other.

The little board covering the aperture in the door of my cell again moved, and the eye of the sentry reappeared, and so it went on at regular intervals all through the night.

How unbearable it all was!

All at once comes a loud sound of footsteps on the stone floor of the corridor. ‘It must be the change of sentries,’ I think. Suddenly the door of a distant cell is heard to open. What can it be? Is it the prison director arrived? Why should he visit the cells at this hour of the night? I listen attentively. Yes, it is he making the round of the cells. He comes to mine. He opens the eyehole and looks in. He passes on, and at the next cell he makes an observation to the prisoner. Yes, it is the voice of the prison director.

41

42

I must admit he was a most faithful servant. All day long he had been on his legs, and now, in the middle of the night, he again made his rounds.

Another hour passed before I could fall asleep. It was no sleep, however, but rather a long line of dreams, interrupted by frequent awakenings.

Some one in the distance was now crying hysterically. At first the sounds were muffled (the sufferer was evidently endeavouring to suppress his cries), but gradually they became louder and louder, and at last the poor man could not restrain himself any longer, and wept aloud in all the strength of his grief and suffering. My own heart was so wrung with pain that I was ready to burst into tears myself. Oh, how sad it was! Would no one come to soothe the unhappy sufferer? I rose with the intention of helping him, but was soon tossing helplessly again on my bed. I hid my head under the bedclothes, but failed to shut out the sound of the cries.

An hour or two passed, and the cries not only did not cease, but increased in vigour. They were hysterical cries of an absolutely feminine character.

How long would this last?

I tossed about in agony until the dawn, when at last I had an interval of rest.

42

VII DESPAIR

‘Everything here is so silent, lifeless, pale;

The years pass fruitless, leaving no trace;

The weeks and days drag on heavily,

Bringing only dull boredom in their suite.’

N. A. Morozov.

Loud knocks at the doors of the cells awoke me. It was day. Scarcely had I risen, and put on the grey trousers and the grey gown, when the soldiers entered my cell, fastened up my bedstead, and, putting a piece of bread on my table, left as quickly as they had entered.

Exhausted by sleeplessness and the horrors of the night, I had no inclination to eat, and sadly sat down on the footstool. I was no longer in yesterday’s state of mind, and the desire to reflect on abstract matters had passed away. My head was aching as from charcoal fumes. I longed to lie down again and go to sleep, but my bedstead was put back. What was I to do?

A feeling of mental weakness and despair crept over me. I could resist no longer, and, laying my head on my hands, I burst into tears.

43

44

As I did not wish the sentry to be a witness of my tears, I squeezed myself into the corner near the door.

A loud knock at the door called me out. The sentry wished to draw my attention to the fact that I must not hide, but remain all the time visible to him.

‘What strange people!’ I thought to myself. ‘They guard the prisoner, fearing that he may lay hands on himself. But who needs his life, after he has been crossed off the list of the living?’

In order to give no opportunity to the prisoner to commit suicide, the prison authorities allowed him neither knife nor scissors. After the bath his nails were cut by the soldiers, whilst meat for dinner was cut into small pieces before it was distributed.

I had no intention whatever of attempting suicide, but I should have welcomed a natural death, especially at such a moment as I have described, when the sentry would not even allow me to stand in the corner of my cell.

And, as if on purpose to annoy me, he looked into my cell that morning as often as possible. To my relief, I at last again heard the noise of doors opening and shutting. The prison director was once more making his round. For what purpose? My turn came. The director

44

45

entered, accompanied by soldiers and the prison doctor.

‘How is your health?’ asked the latter.

I wanted to tell him of my state of health, of my sleepless night, and of the helpless cries of prisoners which disturbed my rest, but, casting a glance at the prison director and the soldiers, I suddenly checked myself and briefly replied:

‘I am all right.’

The doctor left.

I had a vivid remembrance of my first night in my first prison, where, the following morning, feeling exhausted, I asked the doctor, a respectable-looking, elderly gentleman, to help me. By way of a reply he asked me:

‘Since when have you been here?’

‘Since yesterday.’

‘Yesterday? Ah, then it is natural. One always feels like that during the first few days. Wait another three or four days, and you will feel better.’

He turned from me and went. At that moment I vowed to myself never again to ask anything from the prison doctor.

This one, too, would undoubtedly have consoled me with the hopeful prospect of three days, or perhaps, this time, of a week. God be with them!

The doctor had scarcely finished the round of

45

46

the cell, when the same sound of doors and steps were repeated. Suddenly the director walked into my cell and proposed to me to go out for a walk. I put on my grey cap without a visor, with a large black cross on the crown, and, with a feeling of curiosity, left my cell. A soldier went in front of me and another followed behind, whilst the director himself brought up the rear of our procession. Turning round the prison building, we arrived at a wooden watch-tower, full of soldiers. Underneath were a few doors side by side. One of these doors was opened, and I was led into a narrow cage of about 3 or 4 sazhen* in length, surrounded by a high wooden wall; under my feet was the naked sand and above me the grey, sad sky and the watch-tower with soldiers.

After a while another prisoner was led into the next cage, and so on, one by one. Separated from each other by impenetrable walls, we walked about in our cages in silence. There was not a sign of anything green under my feet. I bent down and lifted up a little white stone, not larger than a pea, when a soldier abruptly entered my cage, and rudely ordered me to hand him over the object I had just picked up. l obeyed. With a look of disappointment at the little stone, he threw it away.

—

* A measure of length equal to 1.167 English fathoms, or about 7 English feet.

46

47

‘You are not allowed to do anything; you must neither pick up nor take anything into your hands,’ he observed severely.

I cannot say that under such circumstances the walk was a pleasant one. Anyhow, the pleasure did not last long, for at the end of a quarter of an hour the director led me back to my cell, escorted, as before, by two soldiers.

Great Heavens! What a killing smell there was in the cell after the fresh open air! How was it possible to live in such a horrible atmosphere?

As if in reply to my question came the sound of the shutting of doors.

How tedious, empty, and heavy this life was, morally and physically!

What an aimless existence! Oh, let me yet breathe awhile in the world!

‘It is too early yet for me to die.’ I remembered the words from ‘The Prisoner,’ by Zhukovsky.

After walking about for a while in my cell, I sat down on the footstool, placed my hands on the table, laid my head on my hands, and remained thus until dinner-time arrived, which was announced by the opening of the little flaps in the doors. When the prison director opened one with his key, it fell back with a noise, thus forming a small table, about 7 vershok long and 4 wide. On it was placed a tin basin full

47

48

of sour-cabbage soup, covered with a plate of kasha. I took my food and carried it to my iron table. Lovers of hot food had to eat their prison dinner very hastily; the metal dishes and the iron table made it grow cold very quickly. The <kasha had, under any circumstances, to be eaten cold. When first in prison, I paid particular attention to my food. I used to analyse it, taste it, make guesses as to the manner in which it had been prepared, think about more tasty things. I looked forward to my dinner with particular interest. I found later on that I was not the only prisoner who had made a study of his food. I had occasion afterwards to question other prisoners who had been in solitary confinement, and learned from them that it was the case with all novices. By degrees one grows callous, and eats the dinner mechanically, unconsciously. I must also add that we were not given provender of the kind to make us eat it with special zeal. On the first day of my arrest, I remember, I did not dine at all. For my supper I was given a basin full of absolutely watery soup. Having tasted it, I burst into tears. A prophetic observation of the staff officer on duty, when we cadets used to throw bread balls at one another at table, came to my mind.

‘Gentlemen,’ he said, ‘be more attentive and respectful to your food, especially to your bread.

48

49

Heaven knows whether you may not one day find yourselves in a position which will teach you the full value of a piece of bread.’

To my own surprise, I soon grew accustomed to the kasha, as well as to the soup, whilst the black bread given us for breakfast tasted more delicious than the sugar-rolls which I used to eat when I was free. It needed a great effort of will-power on my part not to eat my entire daily ration of bread, about one pound and a half, when first brought me in the morning, and so leave none of it for dinner.

How relative everything is in the world! This is a lesson that we learn best in prison.

Having finished my dinner, I had now got through the first half-day. I had to live through the second half, to pass it somehow. My headache was nearly gone, but my general feeling was one of heaviness. I felt no inclination to do or think of anything. There was nothing to look at, either. If I had had a book, I should have liked to read. I should have to ask the director for it, I thought; he does not seem to think of it himself. But I was wrong. About three hours after dinner the director, unlocking the aperture in my door, handed me a book, an illustrated History of Art by Lübke. I was overcome with delight; and, as if wishing to overwhelm me with his attentions, he also brought me a Bible, printed

49

50

by the Lay Press, and a small Prayer Book with a calendar. What riches all at once! In prison one learns how to value things. In my joy I forgot my headache and the sentry with his watchful eye, and, methinks, even the very prison.

50

VIII FAILING EYESIGHT

‘Our thoughts grow dull from long confinement;

There is a feeling of heaviness in our bones;

The minutes seem eternal from torturing-pain,

In this cell, four steps wide.’

N. A. Morozov.

The gloomy autumn days passed, winter followed, the monotonous life within four walls being only interrupted by the receipt of books from the prison library. But they soon became valueless to me, my cell being almost in darkness, as the small window with the dull panes, at a distance of 5 arsheen from my table, lent only a feeble light. After three months of solitary confinement, my eyes as I was reading began to be suddenly obscured at intervals by dark patches, and if I strained my eyesight ever so little I seemed to see golden sparks — a thing which had never happened to me before. Not to be able to read a book when its pages are lying open before one is an agony as great as any that tormented Tantalus. Literally suffering ‘spiritual thirst,’ I implored Heaven to send me a healing light.

51

52

Heaven evidently listened to my prayer, for I conceived the idea of bathing my eyes in cold water. Daily, therefore, mornings and evenings, I filled my washing basin with cold water, and, plunging my head into it, kept it there for ten or twenty minutes. The result was unexpected. My eyesight was soon so strengthened that I could read even the smallest print in my half-dark cell. The care for my physical health I carried farther. I made it an invariable rule to go through certain exercises before sitting down to my meals. I waved my arms and legs, bent and twisted my body, sat down, and even ran about from corner to corner, gathering up the skirts of my prison gown. I imagine that my bent figure, thus clad, must have offered at once a pitiful and a ridiculous spectacle. In course of time prison life makes one grow inert and slow. The extremely limited space and the absence of any necessity for hurry are the chief causes of this deterioration, and, one may add, the natural desire which gradually arises to prolong every action so as to make the time appear shorter.

In order to have more movement, I decided to wash the stone floor of my cell every morning. But how? As soon as I heard the first sounds of the opening and shutting of doors, I seized the rag which used to be given to the prisoners

52

53

to preserve cleanliness in their cells, and hastened through the task before the director had reached my door. The time at my disposal being very short, my pulse began to beat faster, and I felt a little more life in me.

The prisoners constantly complained of the lack of manual labour in the open air. After repeated requests, heaps of sand were thrown into the several cages where we used to pass our recreation-time, and we were told to transfer it with a wooden spade from one corner to another. At first I energetically occupied myself with this useless task, but at last I grew tired of this Sisyphean labour, and found it more amusing to trace relief maps of well-known localities in the sand. This occupation was not unlike a childish game, but it could not be any longer looked upon as physical labour.